You can't change the climate 'with dance, libation or prayer' - John Wesley Powell

'For there is not sufficient water to supply the land.' Pt. 3 of 'Getting Hosed' [resend]

The California gold rush triggered the development of a water management system that favored expansion and economic concerns over reasonable use and environmental justice.

Some prominent critics, like Max Gomberg, a former conservation manager under Gov. Gavin Newsom, argue that the state’s water policies today are still largely influenced by that system, despite official claims to the opposite.

But some American pioneers also challenged the dominant water narratives of their times, such as John Wesley Powell.

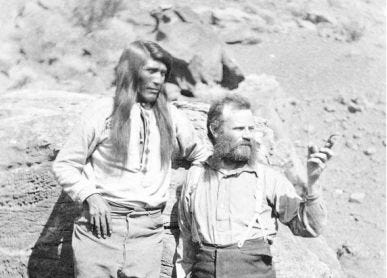

Powell was a geologist and a one-armed explorer of the American West. He gained fame as the first person to travel and photograph the length of the Colorado River for the U.S. government in 1869.

Although Powell believed in Manifest Destiny and was racist and patronizing toward Native Americans, he was also a visionary and a radical thinker, some of whose ideas about water management are still relevant and innovative.

If nothing else, his legacy as a whole, especially regarding water management, shows how much and how little we have learned since he died in 1902.

Powell’s water management system

Powell proposed an ecological (for the most part)1 and equitable approach (except for Native Americans) to developing the West, using natural features like rivers and hills as guides, instead of the checkered squares that we see from the sky today.

According to Powell, a family should only farm 80 acres of land as part of a co-op with other farmers. He also proposed a limit of 2,560 acres of land for grazing per family.

He argued that speculators would take advantage of inexperienced small farmers and gain control over limited water supplies, leading to monopoly ownership in the West.

Within the arid region, only a small portion of the country is irrigable. … The question … is to devise some practical means by which water rights may be distributed among individual farmers and water monopolies prevented. — John Wesley Powell — Report on the Lands of The Arid Region of the United States, 1879

The Homestead Act

The “cultivators of the earth” lionized by Thomas Jefferson were encouraged by the Homestead Act of 1862, which offered 160-acre land plots to small farmers for almost free—more land than Powell believed was practical.

The program failed due to corruption and inefficiency. Speculators and railroad tycoons exploited the land, confirming Wesley’s concerns.

Marc Reisner summed it up in his classic book, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water::

Speculation. Water monopoly. Land monopoly. Corruption. Catastrophe.

The U.S. government paid Powell thousands of dollars to map the water resources of four arid states: Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Montana. He told the Senate in 1890 that those states did not have enough water to support the garden of farms and ranches fantasized about by speculators and the public.

It would be almost a criminal act to go on as we are doing now, and allow thousands and hundreds of thousands of people to establish homes where they cannot maintain themselves.

Powell repeated his warning at an irrigation conference held in 1893:

I wish to make clear to you, there is not sufficient water to irrigate all these lands; there is not sufficient water to irrigate all the lands which could be irrigated, and only a small portion can be irrigated…I tell you, gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict—for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.

Powell’s conservationist ideas for water and land management met fierce opposition from influential congressmen, farmers, and land speculators.

He quit his position as the director of the United States Geological Survey, the federal agency he had proposed to Congress, after his budget was slashed.

But he had accurately predicted the irrigation and development limitations of the arid states he surveyed, and his findings were also applicable to Arizona, Central California, and Southern California.

Reclamation Act

Disasters caused by bad climate and poor water-management in the west spurred eastern speculators to invest in the irrigation of the Colorado River basin and California’s central valley, assisted by government programs that had mostly failed by the 1890s.

The Reclamation Act of 1902, signed by President Theodore Roosevelt, created the modern water-welfare state. It was a grudging admission that Powell had a point: irrigation was essential for any agriculture in the arid West.

The Reclamation Act basically updated the Homestead Act, reflecting the idea that with federal assistance the arid lands in the West could be “reclaimed” for civilization.

Roosevelt saw modern irrigation as a public project that could transform the dry western lands into fertile agricultural zones. He thought that building large networks of canals and reservoirs was “impractical to private enterprise.”

In his congressional address of 1902, Roosevelt praised the Act, stating, “The sound and steady development of the West depends upon the building up of homes therein.”

The Act supported construction of large infrastructure projects in 16 states, including the four-corners states, plus Nevada and California, and it provided low-interest financing for the purchase of cheap federally-owned farmland.

The Reclamation Fund would receive money from water sales, hydroelectricity, and repayments to the government. The fund would support other projects produced by the Bureau of Reclamation.

The program’s participants included politicians who wanted pork, speculators who wanted land, and farmers who were overreaching; they were too ambitious, avaricious, and unskilled to make it work, so it collapsed in bankruptcy.

Still, Reisner wrote, “Every Senator still wanted a project in his state, every Congressman wanted one in his district. They didn’t care whether it made economic sense or not,” and “reforms” only bailed out bad projects.

Through it all, Powell’s dream of equity for settlers failed and California’s native population was largely exterminated by land theft, starvation, disease, and genocide.

In Southern California

Conquering land owners and the growing populations they served sucked the water from California’s groundwater basins, lakes, and rivers like the water would always come.

As Southern California’s non-native population boomed, private and public water agencies formed to minimize water-rights disputes and to keep water and development flowing—often without care for the environment or equity.

In arid Southern California, delivery of water was critical to agriculture and development in SoCal metropolitan centers like Los Angeles and San Diego.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California was formed by Los Angeles and other SoCal cities in 1928 to bring in more water from the Colorado River in order to support future growth.

Franklin D. Roosevelt would greatly expand the purview of the Bureau of Reclamation, not just for California but for the nation; not just to bring water to the ratepayers, but to create electricity for manufacturing weapons during World War II.

A series of huge state and federally funded infrastructure projects were built and the water was delivered from northern California and the Colorado River to Southern California.

Big water projects, mostly dams and canals, would reign in California until 1973.

Today, serious attempts to restart the mega-project approach to conquering nature in the mythical SoCal garden continue in earnest.

And Powell’s warnings about the water portfolios of his time still resonate in the proposed water portfolios of our time:

There are those who would control the rains and change the clouds by boring artesian wells; there are those who would control the clouds by planting trees and preserving forests...and there are those who would control the rains by bombarding the heavens with popgun balloons.... Barbarians add costly offerings...more civilized people add confessions on belief.... But terpsichorean, sacrificial and fiducial agencies fail to change the desert into the garden.... Years of drought and famine come and years of flood and famine come, and the climate is not changed with dance, libation or prayer. — attributed to John Wesley Powell

Next: A brief outline of water infrastructure projects in or for Southern California that led to today’s California water portfolio approach.

Powell believed that forests prevented water from entering into streams and rivers. As a solution, he advocated heavy grazing of the land. John Wesley Powell: The Life and Legacy of One of 19th Century America’s Most Influential Explorers; Charles River Editors