Global warming: the unusually rapid increase in Earth’s average surface temperature over the past century primarily due to the greenhouse gases released by people burning fossil fuels. —NASA

In the Pacific Northwest, including California, much higher than normal temperatures, extreme drought, and explosive wildfires in 2021 were “the beginning of a permanent emergency,” according to Washington’s governor, Jay Inslee.

“We have to attack the source of the problem,” the governor said, explaining how global warming is rapidly changing his state’s economy and culture. “You can’t run from climate change. You have to challenge it and defeat it.”

Climate science shows that without drastic action—now, global warming will inevitably increase by 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) over preindustrial times as soon as 2034, creating spiraling climate-related catastrophe.

“Beyond 1.5, we’re not going to manage on a lot of fronts,” said Maarten van Aalst, the director of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Center and an author of the report. “If we don’t implement changes now in terms of how we deal with physical infrastructure, but also how we organize our societies, it’s going to be bad.” — from NY Times

For decades, climate-change conferences among the world’s leaders, climate scientists, and citizens groups were held—most notably in 1992, 1997, 2015, and 2021—ostensibly to initiate collective efforts for humanity to save itself.

But Greta Thunberg, arguably the world’s most inspirational climate-justice activist, says that those rallies produced more “blah-blah-blah” than substance—and her worldly analysis at COP26 could have pointed to Southern California water districts as an example of blah-blah-blah syndrome at the local level.

This is not about some expensive politically correct, greenhouse, bunny hugging, or blah blah blah, build back better, blah blah blah, green economy. Blah blah blah. Net zero by 2050. Blah blah blah. Net zero by 2050. Net zero by blah blah blah. Climate neutral, blah, blah, blah. This is all we hear from our so-called leaders. Words. Words that sound great, but so far has led to no action. Our hopes and dreams drown in their empty words and promises. Of course, we need constructive dialogue, but they’ve now had 30 years of blah blah blah and words and where has that led us? But, of course, we can still turn this around. It is entirely possible. It will take drastic annual emissions cuts unlike anything the world has ever seen. And as we don’t have the technological solutions [that] alone can deliver anything close to that, that means we will have to change. We can no longer let the people in power decide what is politically possible or not. We can no longer let the people in power decide what hope is. Hope is not passive. Hope is not blah blah blah. Hope is telling the truth. Hope is taking action. And hope always comes from the people.

But what happened—or didn’t happen—at the Feb. 02 meeting of the Board of Directors of the Padre Dam Municipal Water District in Santee might be worse than blah-blah-blah.

Padre’s communications director, Melissa McChesney, reported to the board that October and December had been exceptionally wet months for Northern California (the source for about half of Southern California’s imported water).

A record 212 inches of snow was measured in the Sierra Nevada Lake Tahoe area, she said, but November and January had been bone dry—showing the kind of wet/dry weather cycle predicted by climate scientists.

The Colorado River Basin, which supplies about 55 percent of San Diego County’s water supply, was also going through a wet/dry cycle, she reported.

“March still matters, but January and February are really the key elements of the water year to see what that’s going to look like,” she said.

The state could see the current drought extended to three years with continued water cutbacks from the state.

Inspired, Director Doug Wilson, a Padre Dam administrator and then director since 1989, quipped about McChesney’s rainmaking powers.

In November, he recalled, “I asked you [McChesney] directly to bring us more snow and improve the water conditions, and you did it. December was a record year (sic). So … I’m going to put you in charge of that again now and [to] make February and March a good year (sic).”

McChesney smiled.

But not Director Suzanne Till, who was elected in 2020 and stands out among the five-member board as a professor of water-resources-geography and urban planning.

“Not to be a buzz kill,” she responded, “but in a time of climate change we (scientists at the University of California, San Diego) are going to predict that we’re going to be having much more [climate'] variability. So, you have wet/dry going on and overall less water. So, this is our reality right now and this is why we need to start planning for this.”

Till’s gentle rebuke irritated Director James Peasley, who didn’t like her negativity.

“I’m going to be very optimistic and be positive,” he said. “And I’m putting the burden on Melissa to make it snow like crazy and make it snow in February and March and have a great water year and fill up all the Northern California and Colorado River reservoirs so to the bring such that they are overflowing. So, that’s my hope and prayer and I believe that it all will happen. And I’m a believer in positive thinking.”

Two months later, the hoped and prayed for rain and snow still hadn’t come.

In its April 11, 2022 drought update the California Department of Water Resources reported that:

January, February and March 2022 were the driest on record dating back over 100 years, logging just six inches of precipitation across the Sierra Nevada. That is less than half the precipitation accumulated in the first three months of 2013, which had been the driest in the observed record.

Statewide precipitation for the water year to date is 69 percent of average.

Sierra-Cascades snowpack for the water year to date is 21 percent of average, down from 26 percent last week.

Statewide reservoir storage is 70 percent of average for this time of year.

Data shows the current water year has been marked by climate-driven extremes far outside the historical norm in California. Snowmelt this year began sooner and peaked earlier than seen before.

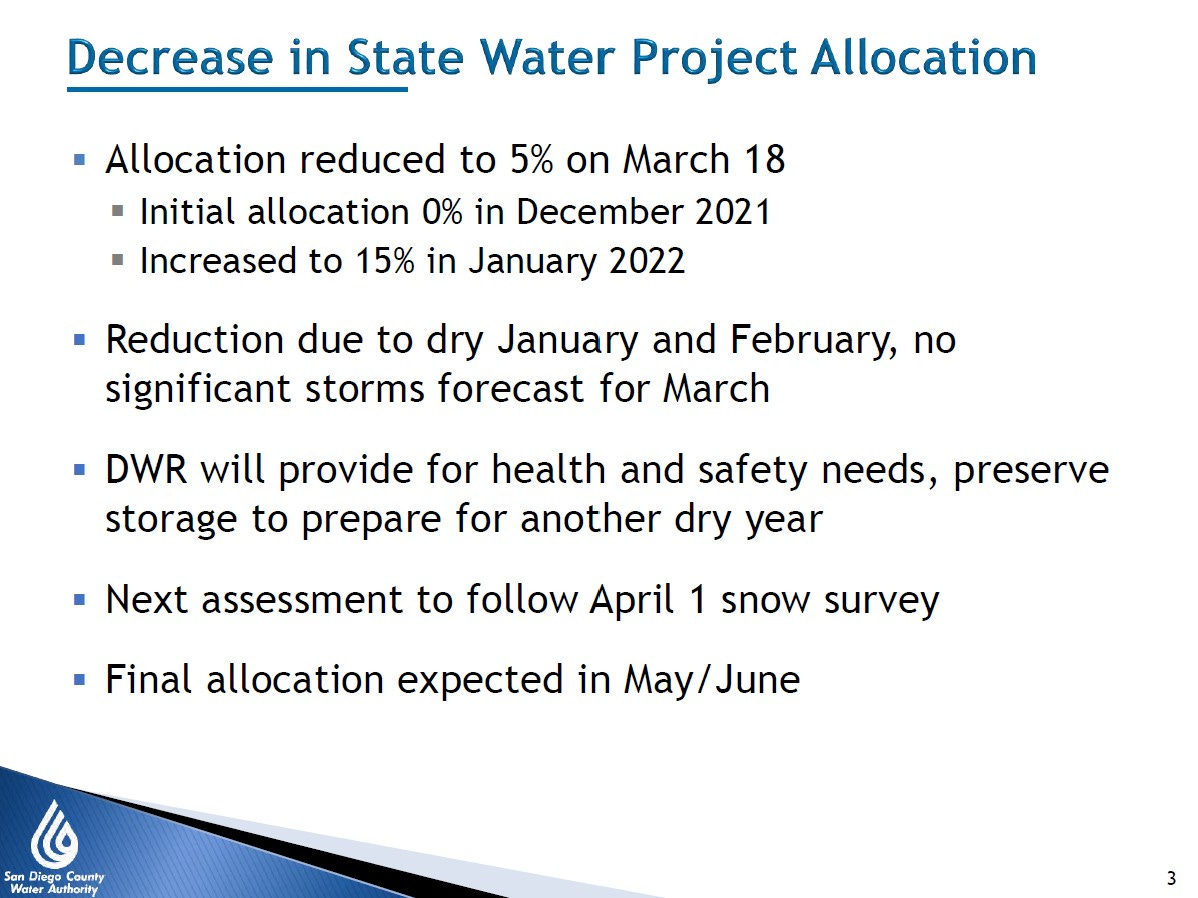

State Water Project allocations went from 0 percent to 15 percent of normal in January following the December rains. But the power of positivity failed to produce enough water in February and March, so on March 18 the allocation was reduced to 5 percent.

San Diego County receives only about 11 percent of its water from the State Water Project delivered through the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and the San Diego County Water Authority, then to the Authority’s 24 retail member-agencies, including Padre Dam Municipal Water District.

And as of March 21, precipitation and snow-water equivalent in the Colorado River Basin was at 99 percent and 97 percent of normal, respectively.

But due to the wet/dry cycle associated with climate change on top of normal drought cycles, Lake Mead and Lake Powell are currently only 33 percent and 24 percent full respectively, triggering agreed upon 2022 water cutbacks for Arizona and Nevada.

Despite a current water glut projected to amply supply the county until 2045 regardless of drought, climate change is “shrinking the Colorado River” to the future peril of the Colorado Basin states and San Diego County.

But there is a potential silver lining to the crisis.

California’s “water-energy-climate nexus” involving all forms of water production provides an “opportunity for integrated management for multiple benefits” that create greater water-use efficiency, thus saving energy and cutting GHG emissions, according to Robert Wilkinson* writing in the book, Sustainable Water: Challenges and Solutions from California.

Most of the savings would come from the end-use of water, especially hot water, by water ratepayers who account for 75 - 100 percent of the water-related use of electricity generated by dams and natural gas (respectively), according to John T Andrew** in the same book.

“Collectively,” he writes, “[water] customers account for 10 percent of the total energy use in the state.”

More important, he notes that “urban water conservation presents the greatest opportunity to reduce the carbon footprint of water in California (California Department of Water Resources 2014).”

In keeping with California and the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) goal of keeping Earth’s average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius or less by cutting GHG emissions to zero by mid-century, many California cities, counties, and at least some water districts, have created climate action plans (CAPs) to reduce GHG emissions in their jurisdictions.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and the San Diego County Water Authority each have a CAP.

(The city of Chula Vista was the first of any government entity in the state to have a CAP in 2000—most CAP’s came after 2006).

The City of Santee also has a CAP.

Padre Dam, Sweetwater Authority, and the Orange County Water District do not have a CAP.

To paraphrase Greta Thunberg, if the existing CAPs rise only to the level of blah-blah-blah, it’s up to the people to turn them into real action, in this case by contacting their local water board, showing up at the board meetings (in person or online), and voting in local elections.

The biographies below were accurate as of 2015, when Sustainable Water was published.

*Robert Wilkinson is an adjunct professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, and a senior lecturer in the Environmental Studies Program , at the University of California, Santa Barbara

**John T. Andrew is assistant deput director of the California Department of Water Resources, where since 2006 he has overseen the department’s climate change activities.

Share this post