Why California’s First-in-World Plan to Monitor Microplastics in Drinking Water Matters

By ignoring the buildup of plastics throughout the natural environment, humanity has been blindly playing Russian roulette with our health and that of future generations.

By Sarah Mosko, guest writer

Every one of us, even unborn fetuses, are continually exposed to microplastics which have become such ubiquitous global environmental pollutants that they now contaminate the everyday air, food and water we take in.

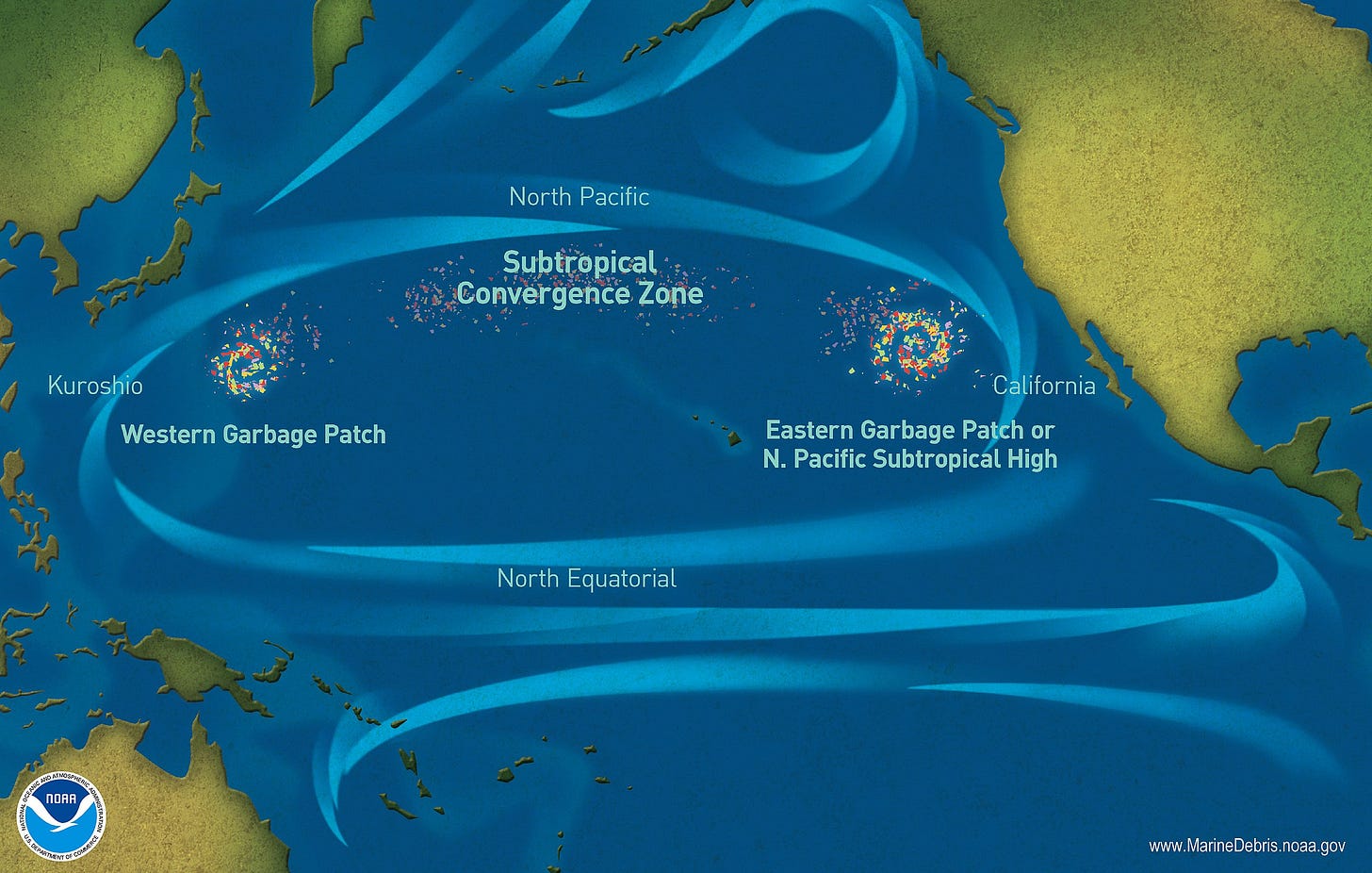

Because plastics are highly resistant to biodegradation – fragmenting instead into ever smaller bits eventually reaching micron and nanometer dimensions – they travel unseen in wind and waterways so that even the most remote regions of the globe, like the Arctic seabed and summit of Mount Everest, are contaminated with microplastics.

Given that global plastics production exceeded 360 million metric tons in 2019 and shows no signs of leveling off, it’s no surprise microplastics (defined as less than 5mm) are increasingly showing up in disturbing places like house dust, beer, table salt, indoor air, drinking water, seafood, plankton, and human poop.

Many constituents of plastics and the pollutants they pick up from the environment are known to be endocrine disruptors, carcinogens or developmental toxins which pose the greatest threat to developing fetuses. Bisphenol-A (BPA)) for example, a building block of certain plastics, was banned nationwide from use in baby bottles and sippy cups in 2012 because its mimicry of the hormone estrogen tampers with sexual development in both males and females. Fetal exposure to phthalates, chemical additives that render plastics soft and pliable, lowers sperm counts.

The placenta in humans has historically been viewed as a reliable barrier protecting the fetus from potential dangers lurking in the mother’s bloodstream. This fantasy has been shattered by shocking revelations in recent decades, like a 2005 report from Environmental Working Group that umbilical cord blood of U.S. babies contains an average of 200 industrial chemicals and pollutants.

That the placenta might also fail to shield against microplastics in the maternal circulation was first suggested by a 2010 Swiss research finding that polystyrene beads up to 240 nanometers crossed through laboratory samples of human placenta. Earlier this year, Italian scientists confirmed that a variety of microplastics, roughly 10 microns and small enough to travel in blood vessels, pass the placenta in human fetuses prior to birth.

Whether microplastics make their way into the body of the fetuses remains an unknown. However, a recent laboratory study in rats showed that nano-sized polystyrene beads introduced into the airway of mother rats translocated not only to other organs in the mothers’ bodies but also to the liver, lungs, heart, kidney, and brain of their fetuses.

By ignoring the buildup of plastics throughout the natural environment, humanity has been blindly playing Russian roulette with our health and that of future generations.

From that perspective, it’s welcome news that California is embarking on establishing the first ever health-based guidelines for acceptable levels of microplastics in drinking water, as specified in the 2018 California Safe Drinking Water Act: microplastics (SB1422). This state law is an extension of the 1974 federal statute which requires monitoring and public notifications of tap water contaminants.

In addition to meeting a July 1 deadline to develop standardized methods for detecting microplastics in drinking water, the California’s Water Board is mandated to conduct four years of statewide monitoring with public disclosure of the results. If the findings of a previous review study of microplastics in drinking water turn out to be representative of our state, Californians can expect to learn we are imbibing thousands to tens of thousands of microplastics annually from water alone.

The law falls far short, however, of designating any obligation or timetable for setting limits on acceptable levels of microplastics or what, if any, measures would be taken if levels exceed those limits.

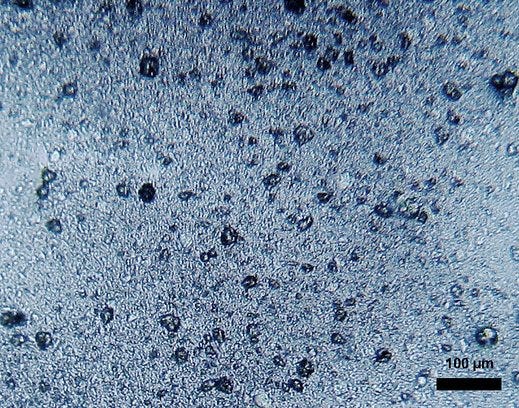

California’s task in implementing the law is nevertheless daunting. There is no scientific consensus yet even on a definition of microplastics in drinking water or how to test for them, and research into the health risks from microplastics in humans (and fetuses) is in its infancy.

Orange County’s water derives from both the local groundwater basin, managed by the Orange County Water District, and pipeline imports from Northern California and the Colorado River, managed by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MET). Both agencies opposed the legislation, though do recognize microplastics as a “contaminant of emerging concern.”

In explaining the opposition, spokespersons from both agencies cited numerous uncertainties they foresaw in executing the law because much of the research needed for implementation had not been done. As example, the State Water Board has yet to inform on such basics as how often and at what sites sampling will occur and how to accredit testing laboratories.

But as stressed by Theresa Slifko, the MET’s Water System Operations Unit Manager, the foundational problem is “there is no solid methodology” to identify and quantify all the types of microplastics in drinking water. Though California is first to mandate monitoring, that there are ongoing international studies, involving dozens of laboratories around the world working to develop standardized methods, speaks to the universality of the problem.

Also looming is a fundamental question of whether conventional approaches to mitigation, such as identifying point sources of pollution or filtering out contaminants, make any sense given the ubiquity of microplastics in the environment and the miniscule dimensions they can assume.

Ocean desalination is not a ready solution at this time either. The abundant microplastics in seawater are already an industry headache because they clog the filtration membranes, and processes being developed to capture microplastics prior to filtration are highly complex and costly.

The public should not be fooled into thinking microplastics can be avoided by drinking bottled water, as studies sampling numerous brands typically discover more plastic debris in bottled versus tap water.

For the concerned consumer, the surest way presently to eliminate microplastics in water is to invest in a whole home or single tap filtering system. Carbon block and reverse osmosis technologies, for example, are highly effective but can be pricey.

While there’s no pathway yet for getting microplastics out of the public water supply, assessing the current load of contamination is nonetheless a wise, proactive first step. Contrast this with the conclusion of a 2019 report from the World Health Organization that “routine monitoring of microplastics in drinking-water is not necessary at this time.”

Assertions that there’s no need to monitor because the threats to human health are unclear (or that monitoring will be costly) remind me of how we barreled ahead producing glowing watch dials painted with radium before the effects of radium exposure were well-defined. Many young women who painted those watch dials suffered radiation-induced illnesses and death.

Radiation is invisible, and that microplastics are largely unseen too is relevant to understanding how we’ve allowed them to so thoroughly contaminate our world and everyday life.

Nevertheless, most of us would refuse a food or beverage visibly contaminated with bits of plastic, even though the risks to health are unclear. It’s just common sense.

Our state legislators who’ve put California at the forefront of addressing microplastics pollution in drinking water should be commended for taking rational precautionary action in the public’s interest.

Sarah (Steve) Mosko writes about contemporary environmental issues for publications throughout Southern California and beyond, including the Surf City Voice. All of her articles are published on her own blog, Boogie Green.