To Nagasaki With Pappy: One Year Before the Bomb (Part 2)

'We don't know where we are and he wants to go back to fire bomb searchlights where this time the anti-aircraft gunners will be prepared and waiting for a single B-29 on a steady bomb run.'

This is Part 2 of my father’s account of a B-29 bombing mission over Nagasaki that he took part in as the flight engineer.

By Robert W. Earl (1920 - 2015)

Pappy turned the huge airplane on its side in a tight turn, forcing our weight into our seats. We still carried the bombs, and any moment I expected to hear them tear loose from the racks and crash through the bomb bay doors. The searchlights followed us into the turn and then lost us. The beams crossed each other outside my window playing back and forth trying to pick us up again.

“We lost them Pappy,” Jack called.

“OK,” Pappy said, after leveling out. “Where do you think that was, Kit?”

“I don't know, Pappy. I can't recognize it. Radar's still not working.”

We had turned 180 degrees and now headed north away from the searchlights while Pappy and Kit discussed whether we were over Nagasaki or some other target. Then Pappy called to me, “How's the gasoline, Bob?”

“It's OK now, Pappy. But let's get the right power setting on these engines. We're burning the gasoline too fast.”

“I gotta have this speed, Bob. I gotta use 2400 rpm for this speed.”

“Pappy, you can have just as much speed with a lot less gasoline if you'd use more throttle and bring down the rpms.”

In B-29s the copilot controlled the rpms by adjusting four toggle switches at the order of the pilot. These switches set the angle of the hydraulically controlled propeller blades of each engine which, in turn, controlled the speed of propeller blades of each engine which, in turn, controlled the speed of propeller rotation. The pilot controlled the manifold pressure of the vaporized fuel mixture entering the cylinders by adjusting his four throttles. Correct combinations of rpms and manifold pressure maximized engine efficiency. With the inherently unsound B-29 engines and the military compromise between bomb load and fuel load, erratic departures from recommended power settings could easily lead, respectively, to overheated cylinders and consequent engine failure over enemy territory or to empty gas tanks on the return flight.

Pappy turned around even farther in his seat and talked again with Kit. That conversation completed, he announced over the interphone that we were going back to drop our bombs on those searchlights. It's the only thing we can do. We're lost and they're probably near some important installation,” he explained.

Good God, I thought to myself. We don't know where we are and he wants to go back to fire bomb searchlights where this time the anti-aircraft gunners will be prepared and waiting for a single B-29 on a steady bomb run.

In answer to my thoughts – and probably to his own – Pappy repeated, “We gotta drop our bombs on something. We might as well drop them on searchlights if we don't know where we are.”

Kit turned to me and asked, “How's our gasoline, Bob?”

“The gasoline is all right if we don't spend more time using this 2400 rpm with meaningless variation in manifold pressure. I can't think of a more inefficient way to waste gasoline. But if we drop our bombs here we should have enough to get home, providing he uses correct power settings from here on out.”

Radar called over the interphone, “I have the radar fixed now, Lieutenant.” Kit scrambled back to his radar scope while Pappy turned the airplane around and headed back toward the searchlights.

“Pappy, I know where we are now,” Kit shouted. “We're way north and east of Nagasaki. We're over Yawata.”

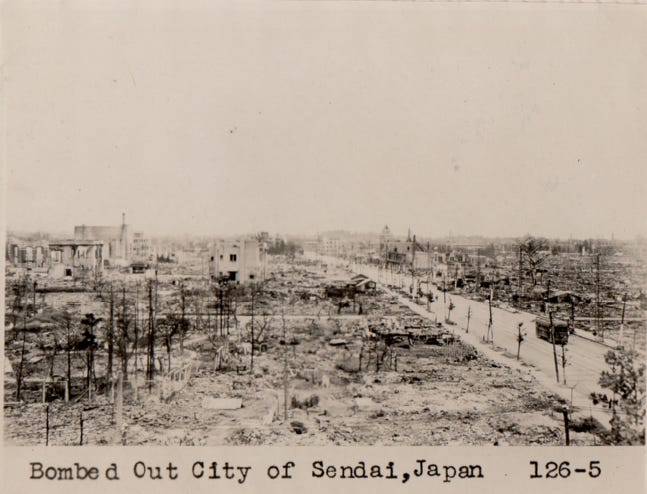

Yawata was the location of the steel mill bombed by our B-29s on June 15, 1944 on the first air raid over Japan since Doolittle.

“How long will it take us to get down to Nagasaki,” Pappy asked.

“A little over half an hour at this speed, Pappy.”

“OK, we'll head for Nagasaki. What's the heading, Kit?”

Kit gave Pappy the heading and then again asked me, “Will we have enough gas now, Bob?”

“Not if he keeps pulling this screwy power setting. Besides, with these crazy engines one of them is liable to go out if he keeps this up.”

I turned to Pappy, “Pappy, let's get a decent power setting on this run to Nagasaki.”

“What shall I pull, Bob?”

“2235 rpm is plenty, Pappy. Otherwise we're going to be low on gas.”

“Well keep your eye on the gas, Bob. Don't let me use too much gas.”

And then Pappy sat back in his seat and made no change.

“God damn it! What's the matter with him?!” I swore, loudly enough that Kit overheard me.

Kit turned to me in genuine horror. “Bob, how can you take the name of the Lord in vain at a time like this?”

This burst of anger from Kit caught me completely by surprise. The irony of the situation for a moment took my mind off our gasoline problem, and I sat back in my seat and laughed at myself as I watched Kit saying a few more prayers to the “Little Lady” riding on his desk.

We had encountered neither searchlights nor opposition for the past twenty minutes, so Pappy reduced his power setting and turned to me for approval as if all the time he had been conforming to my suggestion.

“How's that Bob? Does that look all right? We ought to have plenty of gas now, shouldn't we, Bob?”

“Of course, Pappy. We're been manufacturing it for the last half hour.”

“Whassat?”

“We'll probably have enough gas,” I answered.

“You're doing good work, Bob. You're doing fine.”

Tucker shouted, “I see fire up ahead, Pappy.”

Kit hurried past me to look over Tucker's shoulder.

“I want to come in on this on a reverse heading,” Pappy said. “All the other planes will have dropped on the target by this time and there's no danger of collision.”

“OK,” Kit said, as he gave Pappy the proper heading.

I tried to see the fire out of my window as we approached it, but I could only see the mountains surrounded by clouds. So I crawled up with Kit to watch over Tucker's shoulder, but the bombs had already been dropped and the target had passed out of the sight beneath us. I felt disappointed at not seeing our first Japanese target, but at least we were now on our way home. There had been neither searchlights nor flak. So hopefully, all we had to worry about now was conserving our gasoline to get us home.

Tucker, our bombardier, called to the rear gunners to check the bomb bays for any bombs that might not have been released. The gunners reported the bomb bay empty and the doors closed. Our tail gunner could see the red glow of the fire behind us but was unable to see where our bombs had fallen. Tucker thought our bombs might have dropped a little long but was unable to see the incendiary clusters break open and shower the contents upon the target. And Pappy now switched into the recommended power settings for the trip home.

On our way out from the target area we were able to pick up the U.S. Navy rescue submarine on radar. It had surfaced a few miles off the coast of Japan to rescue any B-29 crew forced for any reason to ditch their bomber in the ocean while coming off the target. Our radio operator, E.J. Rush, reported he had already received a “bombs away” message from the rest of our B-29s. They had bombed Nagasaki 30 minutes before we made our run on the target. Pappy was now quiet and possibly nodding off after all the stress and excitement of the past hour.

Back once more over the mainland of China we passed through the storm again but at much higher altitude than before. Now the rain and updrafts were no longer a threat to our safe passage. By sunrise several hours later we had left the storm and were flying above the overcast. The sky above us was clear turquoise blue and the white cloud layer beneath us reflected the light of the sun in an eye-straining glare.

We were still flying at an altitude of 18,000 feet. So I was unable to open the hatch to the forward bomb bay to check the amount of gasoline remaining in the temporary 640 gallon bomb bay gas tank. By my calculations, however, it was dry. The gasoline gauges on my instrument board reported the amount of gasoline in each of the four wing tanks. But since the amount of gasoline in each of the four wing tanks was getting low, Pappy grew increasingly worried about running out.

The radio compass often used toward the end of a mission to guide us directly to our airfield had gone out of order. And since we were still flying above the overcast our estimated position was based entirely on the flight based calculations of the navigator. If the ground fog still covered our airfield as the latest weather report had stated, we would find extremely difficult to find the field without the radio compass. So while Kit kept track of our position on his maps, Pappy repeatedly called E. J., our radio operator, over the interphone to learn if the radio compass was working again.

To the delight of everyone a range of mountains walled off the cloud cover beneath us, thus leaving this obstacle to our vision behind us as we passed across the mountain wall into a clear view of the ground. But we could find neither distinctive rivers, prominent peaks, nor other landmarks to use as check points and were still forced to estimate our position based on Kit's flight calculations.

Now that we could see the earth below us, Pappy let down to an altitude of 8,000 feet where I could depressurize the crew compartments, crawl into the forward bombay, and check the gasoline in the bombay tank. I found the tank empty as I had already estimated. On the way back to my position I asked E.J. If he thought he could fix the radio compass.

“I don't know, Lieutenant. I'm trying everything I can. It's just a matter of giving me time.”

“OK, E.J.”, I said. “We can always bail out for the thrill of it. What's a little hiking but to cheer us up?”

“Well, listen, Earl”, E.J. Replied. “When we start running out of gas, you tell me. Because I want to be the first out.”

“Roger, E.J.”, I said and headed back to my seat.

Pappy turned and asked me how much gasoline I had, and I told him about enough for a half hour to an hour's flying time.

“I think we are near the airfield, Bob. If only we can get the radio compass working, we ought to be in by that time,” Pappy said.

“Well let's keep up high enough so we can bail out of this crate if we have to.”

E.J. Called up to say that according to the radio weather report the ground fog around our airfield was clearing, and he thought he would have the compass fixed in a minute or two.

The compass came on and Pappy called to Kit to see if he thought it was reading correctly. The compass showed that we were headed directly toward a point immediately south of our airfield while the radio fix from out ground station had put us to the south and east of the airfield. “It's where I think we are, Pappy,” Kit said.

As Pappy maintained our heading in line with the compass reading, Kit remarked to me, “Bob, I hope that compass is right.”

After 30 minutes passed, I asked Kit how long it would be as we had very little gasoline remaining. Kit said he didn't know exactly but thought it would only take ten minutes. So I waited anxiously while preparing to transfer gasoline between tanks in case any engine should run out.

Kit called to Pappy that he recognized the river below us as the one that ran past our airfield.

“OK”, Pappy ordered, “Prepare for a landing, Jack.”

“Have we enough gas, Bob”, Pappy asked.

“If we go into a steep descent or steep bank, Pappy, one ore more engines my cut out. So let's not turn to sharply or use full flaps too soon on landing.”

Pappy wanted an explanation of this. So I crawled up beside him and described as quickly as I could what would happen if the gasoline ran forward or sideways in the wing tanks forcing the remaining gasoline away form the intake leading to the gasoline pump.

“OK, Bob. I'll try not to cut out the engines. But keep on the job and don't let those engines run dry.”

We approached the airfield and entered the first leg of the landing pattern with half flaps. On the next to the final leg, Pappy turned to me and said he was about to use full flaps and again asked about the gasoline.

“I can't be sure, Pappy. But some engines are liable to cut out.”

Pappy called Jack for full flaps and lowered landing gear. As we came in low above the Chinese village, the inboard engines began back-firing and cutting out.

Pappy yelled, “Give 'em gas, Bob. Give 'em gas.”

“Level a little, Pappy. They've got all the gas I can given them.”

“Bob, watch those engines. Bob, watch those engines!” Pappy shouted as he worked the throttles back and forth frantically trying to get the inboards to cut in again.

The plane dropped fast with the loss of power from the two engines, and the whirling propellers cut the top branches of the trees near the end of the runway. In the next few seconds the wheels hit the stone-paved runway just within its leading edge as we safely completed the rest of the landing process.

I looked at Kit and with a wry smile I pretended to wipe the sweat off my forehead. “Well, this is our second great experience. I can hardly wait for the third,” I said. Kit gave an expression of disgust and started collecting his navigation equipment into a briefcase along with the “Little Lady.”

After we taxied back to our hard stand and turned the plane over to the crew chief, the truck came to take us back to the briefing room. As we were riding, Pappy said to me, “Nice work, Bob. You did darned swell on that gasoline.”

I almost felt sorry for Pappy, and came near giving him the compliment he was seeking. But instead I said honestly, “I think if anyone deserves credit for this trip it's Kit. I don't see yet how he found out where we were after only a quick glance at the radar scope.”

Pappy said nothing further as we rode the rest of the way in silence.

Our squadron commander met us as the truck stopped. “Pappy, where have you been all this time,” he asked.

“Well sir, our radar didn't work. We got lost in the storm and ended up over Yawata.”

“I don't understand, Pappy. You mean that you didn't drop your bombs on the target?”

“Yes sir. Kit figured out where we were and we flew down to Nagasaki and dropped the bombs over the target.”

“Could you see any fires, Pappy?”

“There was a large fire. But we couldn't see whether it was in the right area, or not.”

The Colonel set off toward briefing. We followed him inside and received a cup of hot coffee and whiskey. After our separate interrogations and a few more shots of whiskey we rode back to the hostel area for a fried egg breakfast. Finally, half awake, we drifted back to our tents in the warm summer morning to fall instantly to sleep.

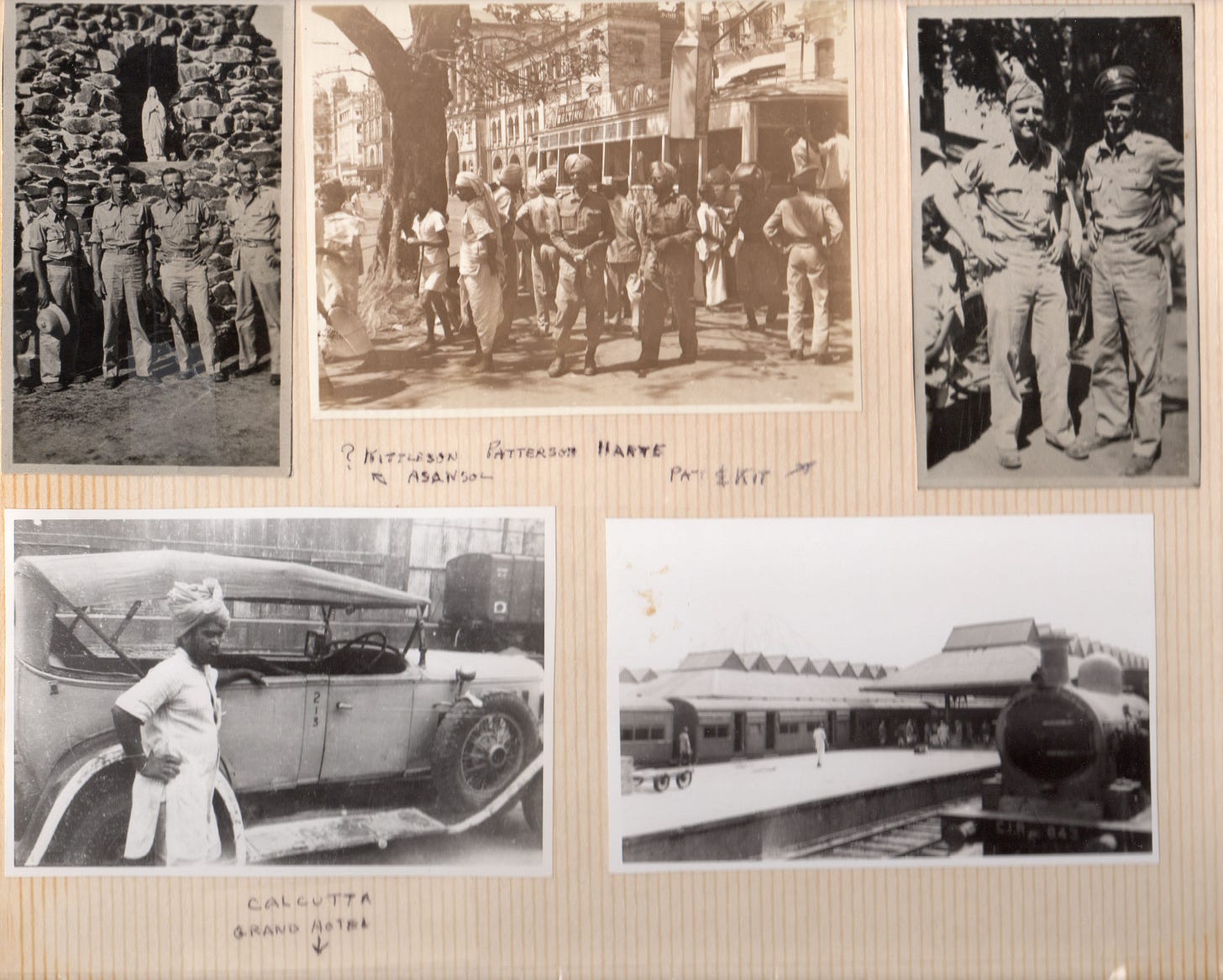

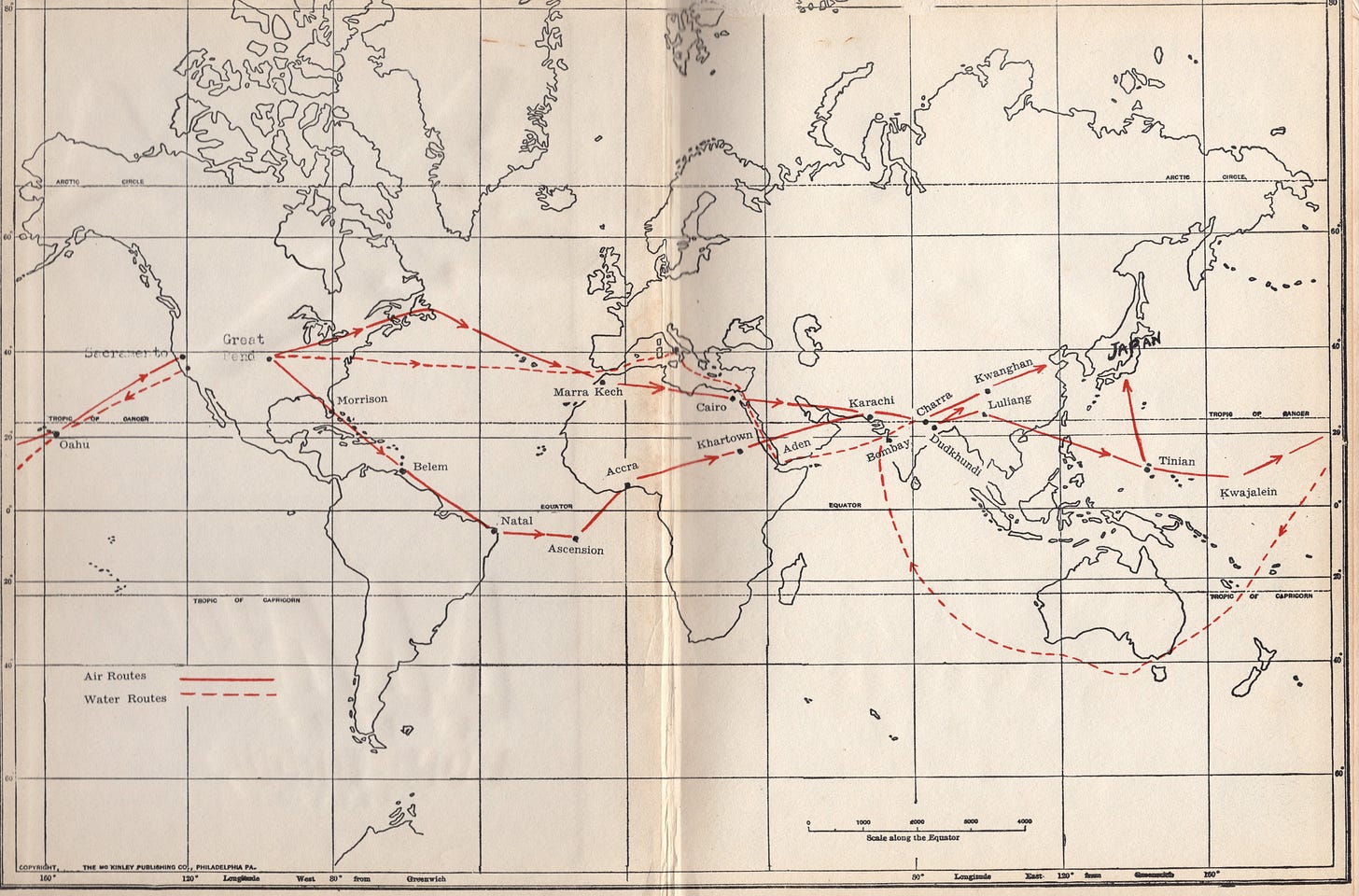

Above photo: October 1943 Great Bend, Kansas training field: Pilot, Captain Milton H. Levitch*; Co-pilot, 1st Lt. John J Harte; Navigator, 1st Lt. Donald J. Kittleson; Bombardier, 2nd Lt. Justin D. Tucker*; Flight Engineer, 1st Lt. Robert W. Earl; Tail Gunner, S/Sgt. Charles W. Tews*, Top Gunman, S/Sgt. Robert Krewson; Side Gunman S/Sgt. Stanley C. Brozoska; Side Gunman, Mazzola; Radioman S/Sgt. Edmon J. Rush Jr.; Later addition of Radarman Sgt. Charles Brennan Jr.* A side gunner replacing ill Mazzola* also dies in that mission (i.e., 5 dead out of 11 man crew). *Died Nov. 11, 1945 in plane crash in Kwanghang (see map below), China on the way to a bombing mission over Omurra, Japan.

Thank you again for writing about the crew of the Princess Eilleen II. My grandfather was s/Sgt Stanley Brzoska. this article is the most i have ever learned about my grandfathers time in the air force. He w never talked much about his time and especially when they had to bail out. I would love to exchange any other photographs with you if possible. wondering if there is a good email i can contact you at.