Poseidon Town: The Beginning

Poseidon’s subsidiary role then as now was to financialize a portion of publicly owned water infrastructure in Orange County for the benefit of Poseidon and its investors

The 20th century iteration of Poseidon Town started with the formation of Poseidon Resources, Inc. (AKA Poseidon Water) in 1995 by venture capitalists from Warburg-Pincus and former General Electric executives, including former GE president Walt Winrow, who was Poseidon’s president until 2008.

Warburg-Pincus is a multinational corporation that in 2005 had investment holdings in 120 companies in North and South America, Asia, and Europe in 2005, according to Hoover’s online.

Poseidon’s subsidiary role then as now was to financialize a portion of publicly owned water infrastructure in Orange County for the benefit of Poseidon and the project’s investors through “public-private partnerships” (PPPs).

At the same time, Poseidon was on a similar track in Carlsbad in San Diego County, a story that I will tell more about as Poseidon Town Through the Wormhole unravels.

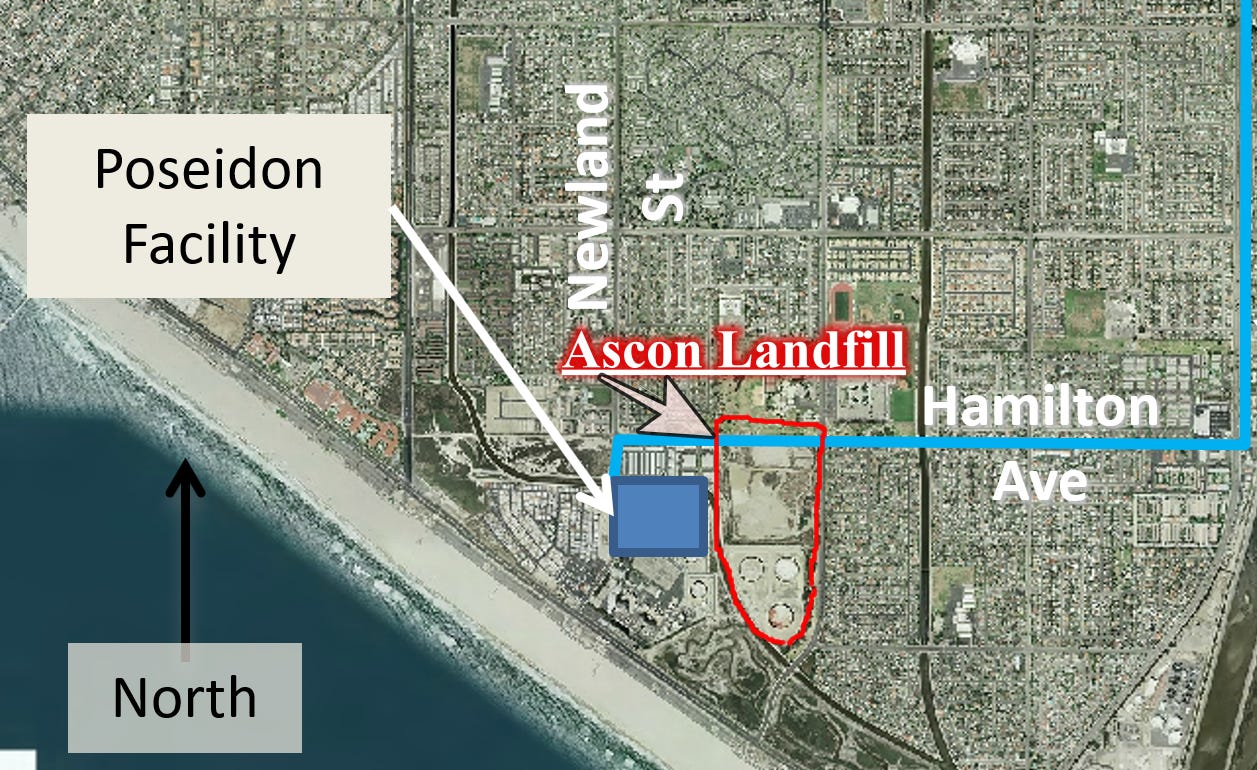

Poseidon’s Orange County mission was to build a $1.4 billion (in today’s dollars) ocean desalination plant on top of an earthquake fault, co-located with a power plant that sits next to the Ascon Landfill, a toxic waste dump in an upper middle-class neighborhood in Huntington Beach, in the middle of a predicted climate-change induced flood zone.

To maximize efficiency and profits, Poseidon chose to co-locate with the AES power plant located on Newland Ave. and Beach Blvd. in order to use its seawater-intake cooling system to suck up about 100 million gallons of seawater for conversion to 50 million gallons of drinking water per day.

That mission remains unfulfilled but ongoing today, nearly 20 years later.

Poseidon Resources probably began taking its project proposal to officials of the City of Huntington Beach, the Orange County Water District (OCWD), and the Municipal Water District of Orange County (MWDOC) sometime in 2001 or earlier, about when Poseidon began preliminary studies of the project site.

Poseidon representative Virginia Grebbien was present at the April 4, 2001 OCWD Board of Directors meeting, according to official minutes. In 2002, a year later, she became OCWD’s new general manager and used her new position to push for the Poseidon ocean desalination project.

Poseidon bragged that it had successfully completed eight other PPP water treatment and reclamation projects collectively worth $2.8 billion in the United States and Mexico at that time (2003). The list included a waste management facility in Cranston, Rhode Island, the Tampa Bay, Florida, ocean desalination plant, and several projects in Mexico for PEMEX, the country’s state owned oil company.

Poseidon’s main selling points were the same then as now: we’re running out of water; its project would create a drought proof water supply; it’s high-priced water will soon be cheaper than imported water; and, a public private partnership puts all the risk on Poseidon and provides enhanced financing opportunities.

In June, 2003, acting now as OCWD’s general manager, Grebbien urged a joint workshop/meeting of OCWD and MWDOC to “outline a common effort with respect to desalination,” including consideration of entering into a water purchase agreement with Poseidon Resources for desalinated water that could be pumped into the over-drafted groundwater basin to protect against seawater intrusion.

OCWD was already planning its Groundwater Replenishment System (GWRS) that now turns 70 million gallons of sewage water into drinking water per day (Poseidon would provide 50 million gallons) at far less cost than desalinated ocean water.

MWDOC director Eric Bakall wanted to conduct a study of the potential need, if any, for the Poseidon project and the reliability of imported water supplies provided by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California before negotiating a purchase agreement with Poseidon. OCWD director Wes Bannister, a former Huntington Beach city council member and mayor, wanted to get right into negotiations with a different developer, Shea Construction.

But both boards voted to do the study instead.

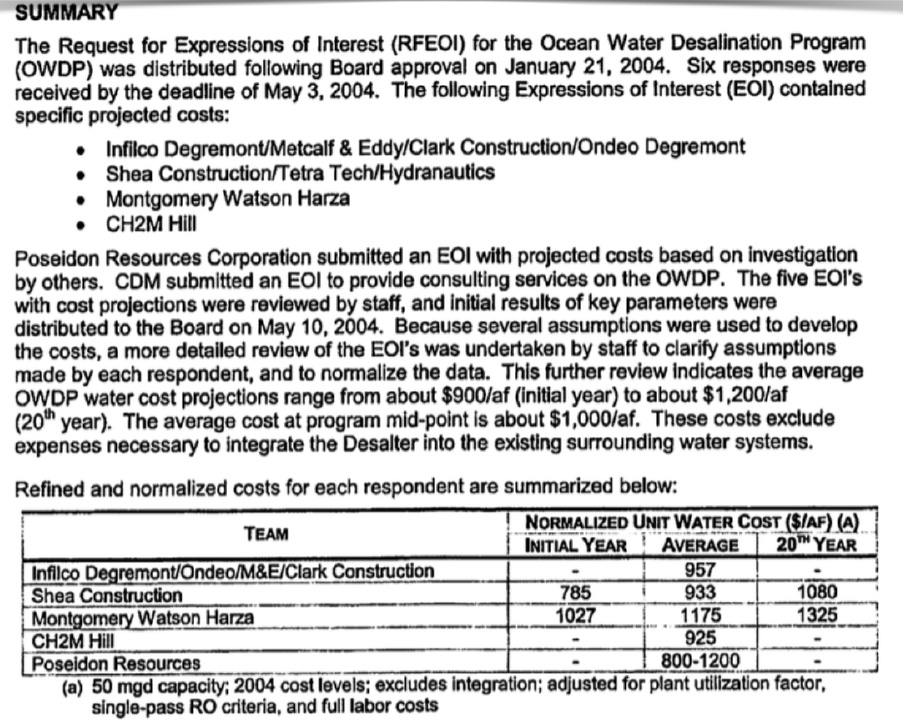

That study, the Ocean Water Desalination Program Concept Development Paper, completed in 2003, assumed a complex “fast track” approach in which the project, which would produce up to 50,000 acre-feet of drinking water a year, would be built by a private company selected through a bidding process and then operated jointly by OCWD and MWDOC.

The study also assumed that OCWD would have a 109,000 acre-foot water shortage starting in 2025.

It concluded that desalinated water could deter potential seawater intrusion into the groundwater basin, but that [far cheaper] imported water supplies from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) could already fulfill that task.

But the study also prompted a strong letter of concerns from OCWD’s groundwater producers group (comprised of 19 agencies that pump groundwater from the basin and pay to have it “replenished” with imported water as needed), including:

lack of substantiated cost estimates;

an assumed MWD subsidy “will probably not be available;”

the study assumes revenue shifting from other OCWD basin management programs that would increase the RA (amount producers pay to replenish the basin), making the study’s desal cost estimates “somewhat deceptive;”

the high price of the desalinated water even with the subsidy and other assumptions;

the use of desalinated water to fortify the seawall would require an additional 50,000 acre-feet of pumping by inland producers, giving them an impossible financial burden to build new wells, pipelines, and pump stations—costs that were not discussed in the study;

private/public partnerships do not lead to cheaper projects. “In fact, public entities can borrow at tax-free rates, which tend to be far below the best taxable rates available for private companies…Private sector equity financing will have an even higher cost of capital, since shareholders have to be compensated for the additional risk through higher returns on investment.”

future water demands are overstated and “appear to contradict MWD’s most current report on water supplies and clearly doesn’t account for supplies under development (reclaimed, transfers, other local projects, conservation) and increased flows of the Santa Ana River.”

cost estimates for unresolved system integration issues (need for new pipes) are based on faulty data and energy costs for newly required water conveyance systems are not provided. Also, impacts of the project on sodium and chloride levels in the water supply could reduce reclaimed water supplies and “the net yield of the project.”

other feasible site locations beside the AES site should also be considered.

In January, 2004, OCWD sent out a request for letters of interest (EOIs) and five companies, including Poseidon, responded with project cost-estimates. Their bids were made public by the board on May 10, 2004. Poseidon Resources was not the least expensive or the most experienced.

Coming up in Poseidon Town Through the Wormhole: The True Cost of Poseidon’s water, Resistance Builds in Poseidon Town, and Poseidon Town’s Environmental Justice Façade.