Padre Dam Municipal Water District in Historical Perspective

Progressive change in water management means overcoming age-old traditions. Padre is just one example.

Officially formed in 1976 by the merger of two local water districts, Padre Dam Municipal Water District’s (Padre) historical roots start with Spain’s colonization of “California” and the founding of Father Junipero Sera’s first of 21 missions, San Diego de Alcala, in 1769.

Padre gets its name from the Old Mission Dam, built during the first two decades of the 1800s by the mission’s brutalized indigenous slaves following a rebellion in 1775 that destroyed the mission edifice and killed two of its administrators.

The 12 ft high 220 ft long dam with its tiled five-mile-long flume was the first major irrigation project along California’s coast. For a short time it was a reliable source of water for the mission’s 1,500 church officials, soldiers, and slaves living in a drought-prone climate.

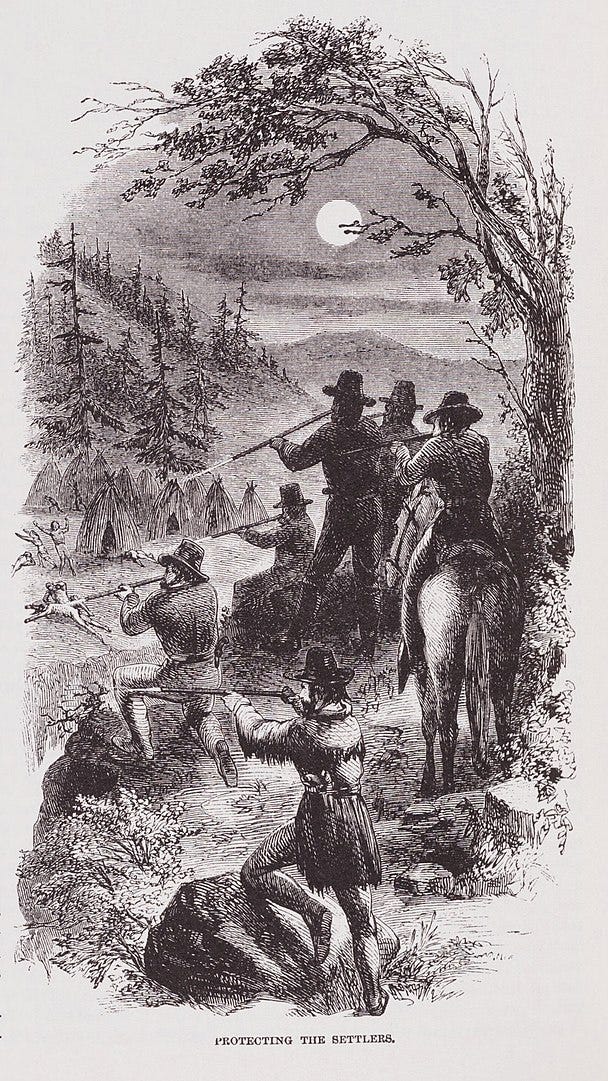

Paternalistic Spanish colonists were displaced by rich cattle ranchers after the war for Mexican independence (1810-1821). Then came the gold miners, developers, and American homesteaders after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848).

In the mid to late 19th century, flocks of European Americans were lured westward by land grants; small ones for homesteaders, huge ones for railroad companies.

Rich and poor alike believed they would build empires on the land they were given, but that land had to be irrigated to be fertile and sustainable, warned John Wesley Powell, the preeminent explorer and water-scientist of the time.

Still, the seekers of fortune, inspired by the theory that “rain was bound to follow the plow,” were fanatical in their quest.

But science prevailed and the water didn’t follow the plow.

Marc Reisner summed up the situation in Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water:

Speculation. Water monopoly. Land monopoly. Corruption. Catastrophe.

Instead of profits and paradise, severe droughts ensued. The land barons sucked the water from California’s groundwater basins, lakes, and rivers down to dangerously low levels.

Then they demanded taxpayer funding for dams and canals that delivered water from the Colorado River and Northern California’s lakes and rivers to rapidly growing populations in the southwest, especially Southern California.

Today, the Colorado River ends in a trickle and every significant river in California but one has been dammed. Watersheds are severely diminished along with fish and other wildlife populations. Groundwater basins are even more overdrawn and we are in another major drought—exacerbated by climate change.

Through it all, California’s native population was largely exterminated by land theft, starvation, disease, and genocide.

Following failed attempts in 2010 by Padre to build a water pipeline through Kumeyaay burial grounds, the mission era’s descendants now work closely with the district on local water issues.

Today, Padre provides water for 113,000 residents in east San Diego County, including the communities of Santee, Flynn Springs, and Alpine Heights. The water comes mostly from the Colorado River via the San Diego County Water Authority (CWA), but the district plans to build a $640 million waste-water purification facility that will serve 30,000 of those residents with potable recycled wastewater in the near future.

Water districts were created to minimize water-rights disputes between large landowners and to keep development flowing, often without concern for the long-term environmental and economic consequences.

The top priority of water districts is to sell water. They are an industry in their own right. Padre’s purification project and others like it directly challenge the dominance of the CWA, with significant potential impacts for the county’s water ratepayers.

Water is owned by the public. Water districts hold that water in the public’s trust and and by law answer to the public.

But few ratepayers ever see their local water board in action, nor are they encouraged to. And their directors (many of whom are retired or financially independent) act as a coterie and typically hold meetings at times convenient for them but not their working class constituents.

A new Padre water board director, Suzanne Till, and her supporters, recently challenged that tradition and the rest of the board responded, after some tense discussion, positively.

More on that, next.