Looking for South Bay's 'political machine' and why we should care if there is one

A journal of political discovery - #2: 'Money and power bind them together.'

Note: A correction has been made. Chula Vista Councilmember Jill Galvez was not termed out in the 2022 election. She ran for mayor and lost that race to John McCann.

In my first journal entry I asked Bing AI to define the term “political machine.”

For my purpose, it’s a pejorative term used to describe a “party organization that is headed by a single boss or small autocratic group” that uses “tangible incentives” to control politics in a local area.

Then I asked if there are any political machines in San Diego County.

Bing AI said no.

But I had read articles about two rising political stars, Jesus Cardenas, the first chief of staff for Stephen Whitburn, who was elected to San Diego’s city council in 2020, and his sister, Andrea Cardenas, elected at the same time to the Chula Vista City Council, representing District 4.

For years, brother and sister ran the now defunct political consulting firm, Grassroots Resources, with Jesus at the helm.

As a whole, the articles implied that Cardenas & Cardenas ran a Democratic Party machine based in the county’s South Bay region, which includes Bonita, Chula Vista, East Otay Mesa, Lincoln Acres, National City, and South San Diego.

Who cares, anyway?

What if there was or is a political machine in the South Bay? What does that have to do with SoCal water wars, the name and topic of this newsletter?

It matters because, as the late U.S. House speaker “Tip” O’Neill used to say, “All politics is local.”

Machine-run or not, most of us barely pay attention to our local or regional water districts. Still, the nexus between water and survival reveals itself at all political levels—and we would ignore that at our peril.

True, water districts seem to function more as lucrative side-jobs for connected businessmen or repositories for fading politicians than springboards for higher office.

But local city council and school board positions can lead to other good or great things for aspiring politicians—just look at Pete Buttigieg, for example. So, too, can water board positions lead to other political and economic platforms.

Consider Denis Bilodeau, who has served on the Orange County Water District Board of Directors without interruption since November 2000. OCWD has great per diems ($315x10 monthly), health care, dental, life insurance, and computer equipment funding—worth about $67,000 a year in combined pay and benefits.

While serving on the board, he also held positions on the City of Orange City Council (2006 - 2014), Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority, Orange County Vector Control, Orange County Waste Management Commission, Orange County Transportation Authority, San Joaquin Hills Transportation Corridor Authority, Foothill Eastern Transportation Corridor Authority, Orange County Sanitation District, Orange County Water Task Force, Orange County Housing and Community Development Commission, and the Los Angeles and San Gabriel River Watershed Taskforce.

Some of these positions offer a nice stipend, if not benefits, and they all can increase one’s political clout over the years.

Or Harry Sidhu, “a small businessman” (supposed Pollo Loco tycoon) who “knows how to balance the books.” He was elected to Anaheim’s city council, then as mayor of Anaheim.

He also served two appointed terms on the OCWD board of directors while sitting on the council; 2012-2015, and again from September 2021 until May 2022 when an FBI investigation of corruption, related to the attempted sale of Anaheim Stadium, caused him to resign.

Or Shawn Dewane, an investment consultant, who has served on the Mesa Water District Board of Directors since he was appointed in 2005. He has been a passionate advocate of the “abundance” and “every tool in the tool shed (portfolio)” doctrine of water management.

Dewane also served concurrently on the OCWD Board of Directors from 2010 until 2018, despite California’s Govt. Code Section 1099, which prohibits public officials from representing two offices with overlapping jurisdictions and conflicting duties.

In 2010, Mesa Water incorporated CalDesal, a non-profit group that lobbies for the desalination industry. Official Mesa Water minutes show that Dewane pushed hard to become Cal Desal’s first Chairman of the Board, a non-paying position he held for years.

CalDesal and Mesa Water worked closely with Poseidon and the OCWD to promote the proposed $1.4 billion Huntington Beach ocean desalination plant that was ultimately rejected by the Coastal Commission.

Dewane also serves on the Board of Directors of the Orange County Employees Retirement Systems.

In the 2018 election he lost his OCWD seat to Poseidon opponent (and former OCWD board member) Kelly Rowe. Luckily for Dewane, his seat on the Mesa board is considered safe, proving that a varied political portfolio increases income reliability.

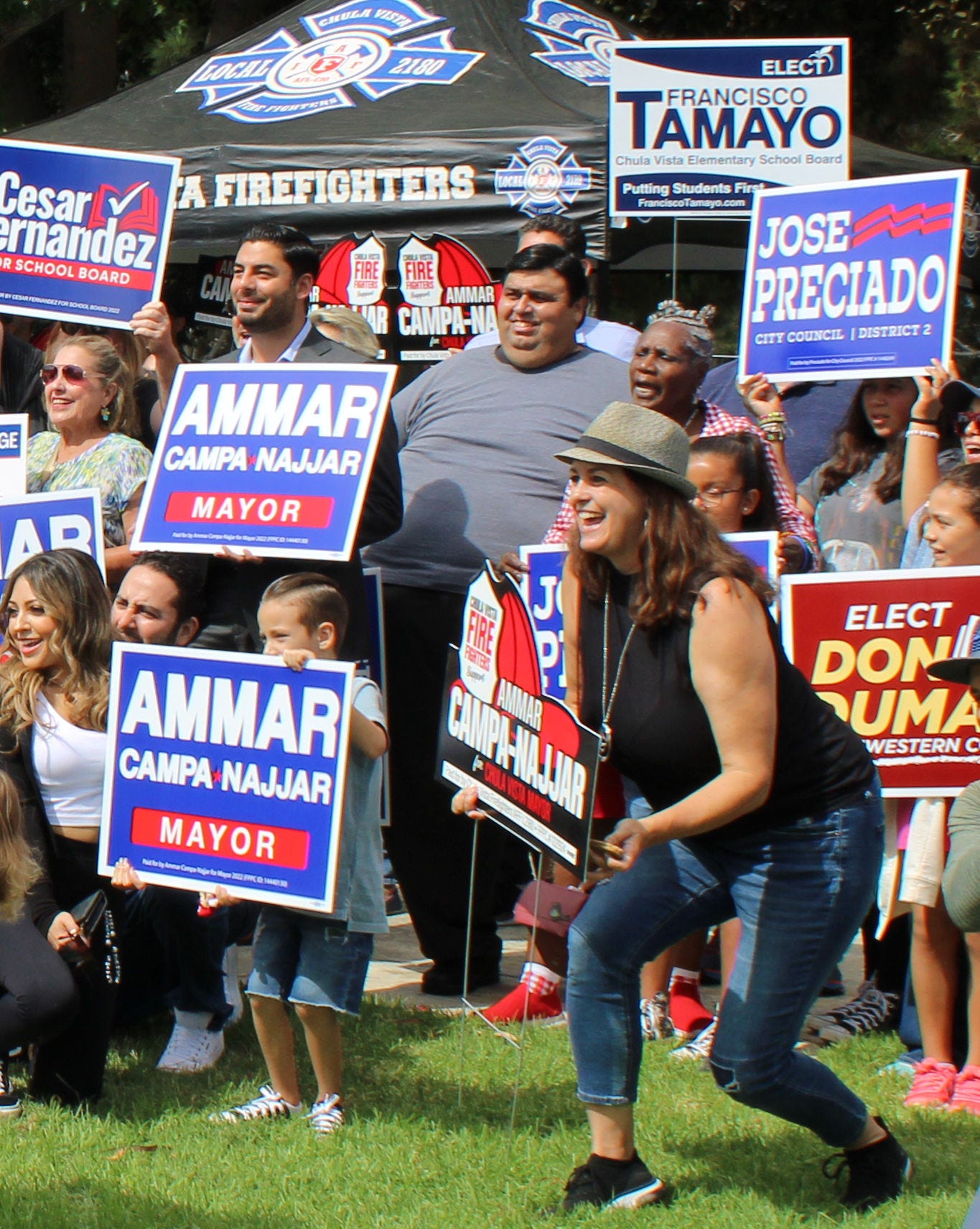

Coming back to the local basis for this journal, consider the election of former South Bay Irrigation District board member Jose Preciado to the Chula Vista city council, replacing conservative democrat, Jill Galvez (who ran for mayor and lost), in District 2.

Preciado ran for office on an affordable housing and crime-reduction platform.

He is a dean of undergraduate studies at San Diego State University. While serving on the SBID and Sweetwater Authority joint-powers water board he earned at best about half in per diem and benefits that OCWD board members get.

Relatively speaking, that’s a rags to riches story because at city council he gets a base pay of $60,490, plus travel and other expenses paid—probably enough to keep him out of the local homeless shelter if not for his university job.

Successful career politicians step up, across, or down from one platform to another, hoping they won’t be forgotten by old allies and that they will make new ones.

Money and power is the glue that binds them all together.

You could write a book about these water hogs and the influence peddlers that keep them in office. Please don’t stop there.