Irvine Ranch Water District pushes portfolio-based water planning, including conservation

But conservation isn't always the best answer, says IRWD's resource planner, Fiona Sanchez

Three distinguished panelists were recently asked by the Southern California Water Dialogue to respond to the question, “Can we conserve our way out of this drought?”

The first two panelists were Max Gomberg, former conservation manager for the California State Water Resources Control Board, and Tracy Quinn, a member of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California Board of Directors.

The third responder was Fiona Sanchez, Director of Water Resources for the Irvine Ranch Water District, which serves 600,000 ratepayers in central Orange County.

Sanchez has spent most of her career advocating for conservation, but she wondered if the panelists were being asked the right question.

“Because I’m wondering why we had a drought emergency just a few years ago and now we’re in another one,” she said. “Why are we constantly going to emergencies?”

Climate change is a reality, she says, “but it’s not something we learned about just last week.”

Like all water suppliers, IRWD’s goal is “to meet our customer demands.”

So we have to ask, “Are there some underlying issues that we need to address” and “What are the tools to get through the drought and meet our long-term goals as water suppliers and as a community?”

The answer, Sanchez believes, is that water conservation is a major part of the solution to water reliability but it’s not always the only or best solution.

Good water management is like good car maintenance, Sanchez reasons. When she takes her car to the mechanic, she wants to “use all the tools in the toolbox to figure it out” in order to prevent recurring future problems.

Of course, some auto-mechanics use unneeded tools to repair non-existent problems or overcharge for real problems that they failed to fix (My words, not hers).

Like the $1.5 billion Poseidon Water ocean desalination project for Orange County, which IRWD played a big role in defeating last May.

What’s In the Toolbox?

The toolbox approach, academically known as portfolio-based planning, is about “how to combine water management actions for greater effect,” as Ellen Hanak and Jay Lund explain in the book, Sustainable Water, published in 2015.

Portfolio water planning is like a mutual fund, intended to “balance risks and returns through diversification,” they explain.

An inexpensive water conservation option may help avoid expensive expansions in supplies (sometimes called ‘avoided cost’). But extreme levels of water conservation can be more costly than judicious use of other water management activities.

In theory, portfolio water management includes a wide variety of integrated and cost-balanced options based on complex computer modeling, divided into three broad but overlapping categories (adapted below from from Hanak and Lund):

Demand allocation options, including (partial list):

urban conservation

agricultural-use efficiency (conservation)

recreation water-use efficiency

induced “shortages”

Supply management options, including:

groundwater storage

expanding infrastructure (conveyance, recycling);

stormwater collection

desalination

General policy tools, including:

water pricing (tiered rates, etc.);

subsidies, taxes

water markets

public education (outreach)

IRWD’s Conservation Dilemma

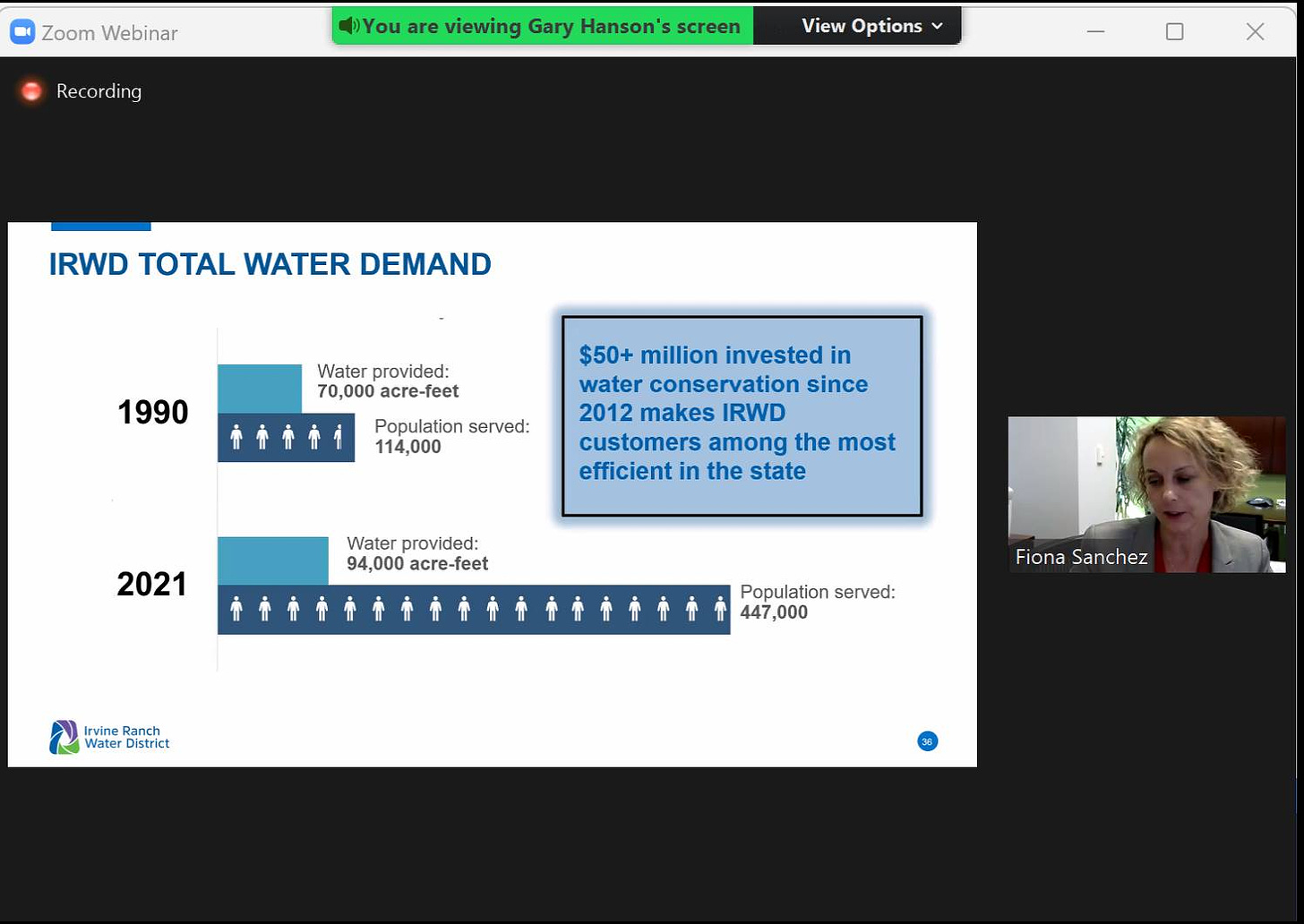

IRWD has a tiered water rate system that discourages waste and encourages conservation, and it spent over $50 million for conservation projects since 2012, Sanchez said.

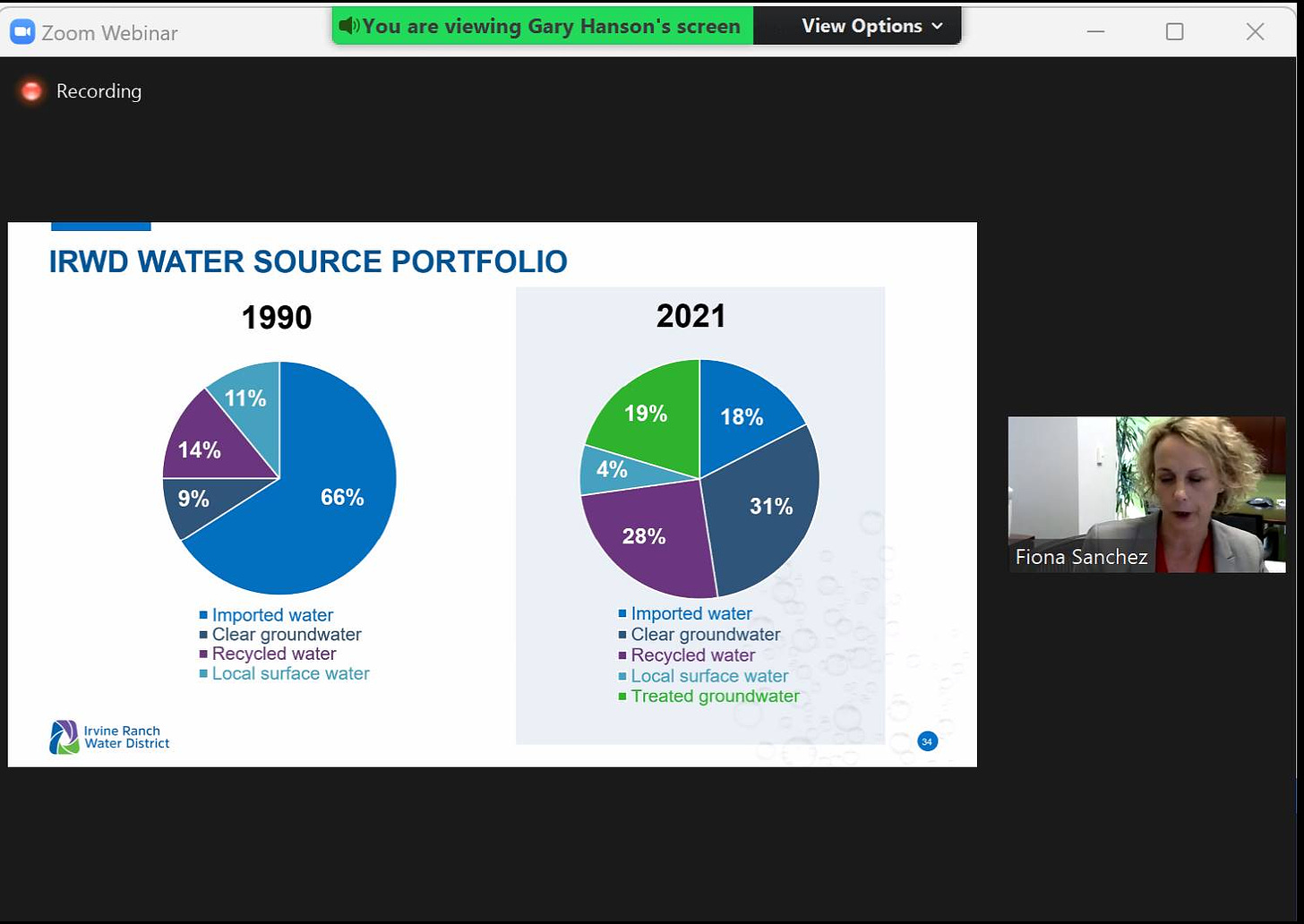

That and other investments in groundwater wells, water recycling, surface reservoirs, and emergency storage provided IRWD with ample water supplies.

In 1990, IRWD provided 70,000 acre-feet of water for a population of 114,000. Today, the water district serves a population of 447,000 with only 94,000/AF of water, reflecting a trend that has occurred more or less throughout Southern California.

“We looked out into the future and made some smart investments, and so we are resilient,” Sanchez explained.

Authors Hanak and Lund don’t cite any actual cases of “extreme levels of conservation,” but Sanchez gives examples where conservation can make it harder to afford local investments in other water resiliency and efficiency projects.

During the previous drought in 2015, after voluntary water cuts proved insufficient, Gov. Jerry Brown mandated water cuts of 25% with some exceptions for water agencies that had created sufficient reserves.

IRWD wasn’t allowed to use its emergency storage, Sanchez said. “Our customers made significant investments and yet we still had to tell them we had a [water use] cutback.”

Sanchez says that officials from other water districts questioned why they should make the same water-supply investments that IRWD did, including conservation, only to face cutbacks as their reward.

Last April, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California declared a water shortage emergency and restricted outdoor watering to one day a week in areas of Southern California that depend on the State Water Project for their imported water.

Last May, the State Water Resources Control Board enacted emergency drought polices that require local water districts throughout the state to prepare for 10-20 percent reductions in state water supplies and banned watering of “non-functional” lawns on non-residential properties with some exceptions.

Then last week the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California declared an emergency for all Southern California, including San Diego County, where imported water comes primarily from the Colorado River. If voluntary compliance continues to fail and drought conditions persist for the next several months, conservation will become mandatory.

Imposing water cutbacks this time around would be a hard sell for ratepayers, Sanchez claims, because “we have such a diverse water supply, we’ve had no shortage, [and] we have no projected shortage next year or even a few years out.”

IRWD can and will do more conservation, she explained, but it wants to avoid discouraging future investments in local water resilience and efficiency.

“Instead,” she says, “we should be adopting policies that consider the bigger picture and balance the use of all the tools in the toolbox.”

Testing