Costly Carlsbad desal gambit makes county water buffalos nervous

First in a series of stories about water agencies and ratepayers struggling with past water-management decisions and future needs.

Editor’s note:

In 2011, Conner Everts, one of California’s venerable water conservation advocates, wrote that ocean desalination is dead in California. His essay is posted below.

At about that time, the San Diego County Water Authority, the County’s water wholesaler, signed a 30-year take-or-pay contract with Poseidon Water to build the $1 billion Claude "Bud" Lewis Carlsbad [ocean] Desalination Plant, described hagiographically on the official website.

The project was approved by state regulators and construction began in 2012. The plant started limited operations in 2015.

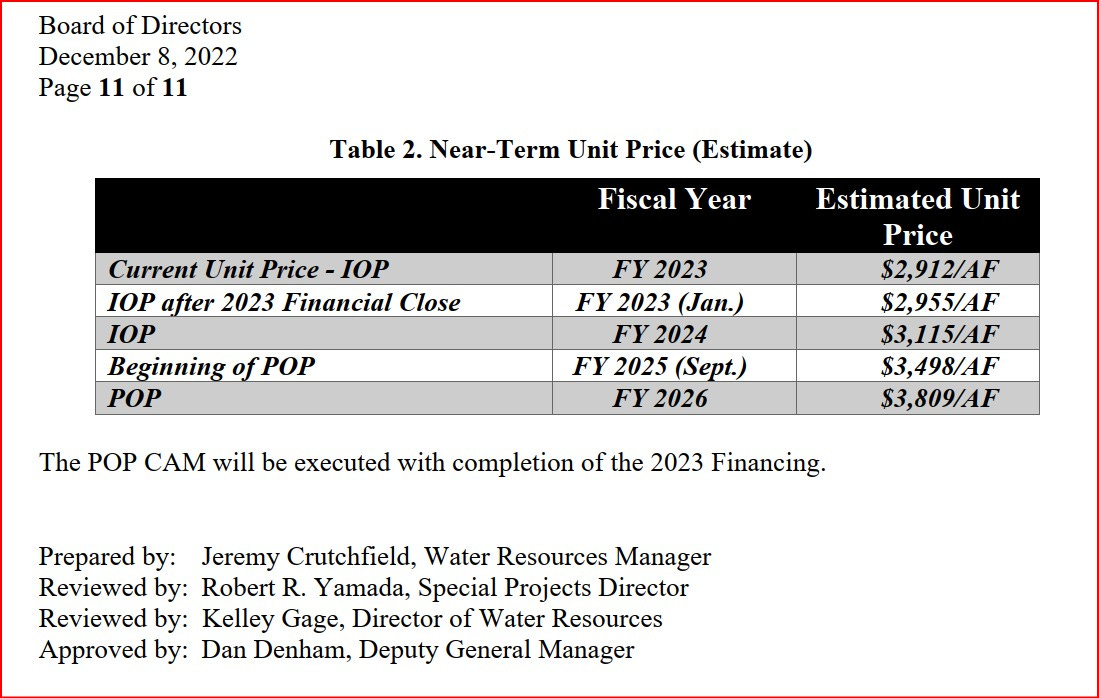

It is the largest ocean desalination plant in America, capable of producing 48,000/AF of potable water per year—water that was predicted in a 2022 report to rise to $3,800/AF by 2026, about 3 times the cost of water imported from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

Poseidon Resources (aka Poseidon Water), the project developer, exploited its public-private partnership with the Water Authority to build the first of at least two large investor-friendly desalination plants envisioned along the California coast.

The Carlsbad plant was a boon for a multitude of investors world-wide—at the expense of ratepayers—as explained in a 2019 study exclusively reported on previously by SoCal Water Wars (you can download it below).

Despite long-given promises of new technologies that would make ocean desalination more economical and eco-friendly, the California Coastal Commission unanimously blocked Poseidon’s plans for a publicly subsidized $1.4 billion ocean desalination plant in Huntington Beach because it didn’t meet those standards.

With that decision, the Commission clearly signaled that large ocean desalination plants won’t be an option in the future but small and more eco-friendly plants were likely to be approved.

Currently, the list of existing or wished-for ocean desalination plants along the coast includes Dana Point (approved in Orange County), Monterey County, Santa Barbara (existing), and San Francisco Bay.

Among the list, only the proposed San Francisco Bay project could potentially approach the size of the Carlsbad plant.

Is ocean desalination dead in California?

No.

But even building smaller facilities is still a financial and existential struggle.

For at least the near future, the most grandiose desal dreams are contained. And the existing Carlsbad plant is imploding, having become a financial Medusa that the Water Authority’s Board of Directors increasingly wants to return—somehow—to its Pandora’s box.

More on that next week.

For added historical perspective, please read Conner Everts' eerily predictive desal commentary written back in 2011 (below).

Why ocean desalination is dead in California

By Conner Everts

Originally published June 27, 2011 in the Surf City Voice and reposted here for historical perspective.

Drinking water from the Sea?

Sounds like a great idea. JFK once said that it would be a greater achievement than putting a man on the moon, and most polls have shown a 70 percent acceptance rate of the idea.

So what is the problem?

The corollary to JFK’s statement would be “when economically and environmentally feasible” and therein is the challenge.

However, the first question that should be asked is, do we need ocean desalination (often called desal) in California and would it hurt or harm the environment compared to its alternatives?

In 2006 there were 29 proposals for ocean desal projects along the California coast, with many attached to old coastal power plants. Now there are only nine.

While industry proponents blame California’s protective environmental regulations and a few environmentalists’ opposition, there were three main issues that stalled the proposals.

First, despite the State Desal Task Force convened by legislation, there is no consensus on a regulatory order or state-wide direction. So each proposal lumbered through the multi-agency process.

That’s as it should be because if there is a large scale desal plant built in California it will be the first on the Pacific coast and largest in the Western Hemisphere.

The first proponent out of the gate was Poseidon Resources, a private corporation from Connecticut that failed with its first desal project – the largest in the nation at 25 million gallons a day – in Tampa Bay, Florida, and then proposed two more plants, each with twice that capacity, one in Huntington Beach in Orange County and the other in Carlsbad in north San Diego county.

Rather blood would be let on the floors of the MWD boardroom before anyone at MWD would give up any sacrosanct water rights.

While working hard to gather political support for its southern California desal projects, Poseidon failed to respond to repeated information requests by the Coastal Commission or to follow its permitting guidelines.

Meanwhile, local opposition grew and water agencies weighed into issues of the marine environment, which they little understood, and were forced to navigate California’s complex and arcane water supply laws as well.

Second, conceived in a time of drought, the most recent crop of desal proposals depended on a fear of limited water supply while demand was high for new development. This was especially true where desal plants were proposed on the coast, thus allowing entry points for previously undeveloped areas with limited water supply.

With the collapse of the global economy, developments now sit idle and the need for desal as a redundant water supply for more growth is being questioned.

Promoted as an offset to water pumped over the Tehachapis and therefore reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the opposite is true.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) states in its subsidy contract that the water produced by desal would not curtail deliveries of any imported water source. Rather blood would be let on the floors of the MWD boardroom before anyone at MWD would give up any sacrosanct water rights.

Furthermore, the promises that these proposed desal plants would offset water taken from the SF Bay Delta turned out to be false. Given the long history of getting water back to fish and the environment, there is no regulatory process to make that happen. Just look at the 20 years of litigation that has taken place over Mono Lake.

Third: first things first.

There are untapped and cost-effective local water resources that must be developed and that have environmental benefits, unlike desal, such as maximizing serious water conservation and water reclamation, capturing and treating urban and storm-water runoff, expanding now legal grey water and rainwater cistern systems, and fixing leaky infrastructure or pipes.

Combine that with a systems approach with watershed management and we begin to get to the point that Australia, Spain, and Israel did before they invested in desal – which meant reducing per capita water demand to 30-50 gallons per day. Compare that to 174 gallons for California as a whole and 121 gallons for Los Angeles.

Many areas across the state, including Los Angeles and Long Beach, have had serious reductions in water demand and eliminated the need for desal—it’s not in Los Angeles’ 20 year supply plan and Long Beach is reconsidering after careful research.

California spent $50 million of Prop. 50 water bond monies on researching this issue and while not all the grant results have been revealed, the emerging consensus is that proponents’ promise of a technological breakthrough to make desal feasible or necessary hasn’t been realized. This is a case of “Its not the technology, stupid, but the lack of economic considerations and available capital.”

And then it rained, and rained, and continues to rain.

Reservoirs filled and spilled.

Snowpack reached record levels in the Rockies, from where a portion of our imported supply originates.

If we had only realized the potential to capture rainwater and redistribute stormwater back into our depleted underground aquifers, this would have been a great winter to replenish the bank of locally stored water.

A quick historical perspective shows that ocean water desal plans come and go in California. In the 60s and 70s it was twin nuclear power plant islands to be built offshore and provide all the water we needed and a small plant that was sent from the navel base in Point Loma to Guantanamo in Cuba.

In the 80s and 90s it was the Santa Barbara plant that was built in the middle of the six-year drought and was idled before it ever was connected by El Niño spring. While it is still being paid for it is more cost effective not to run it.

At Catalina Island in the late 80s a small plant was built as a backup to allow a developer to build condos. It sat idle for many years until Southern California Edison took it over, and in the only place where they sell water it takes 70 percent of the island’s electricity to produce 20 percent of its water.

Internationally, where there is often no other choice, limits have been reached but with a price. Australia is now deeply indebted for billions for plants that sit idle and have been flooded.

Even the Middle East is having problems with desal with huge demands for energy and subsidized water in Saudi Arabia and discharge levels that increase salinity and therefore energy demands in enclosed areas.

Ocean desal is promoted heavily by a cabal of membrane manufacturers, including GE, power plants operators hoping to keep their old fish-killing machines operating, water agencies looking for large capital projects built with some else’s money, engineering consultants and even Las Vegas.

But the bloom is off the issue. It looks good on the outside but once you delve into the inside there are problems, like fast food might sound good at the moment of hunger but the results of eating it are negative. Investing in the current crop of desal plants is like buying an old Hummer with today’s gas prices.

Concerned citizens who organized statewide and locally to inform the public and fight the desalination surge can now declare victory and focus back on appropriate multi-benefit local water resources.

It does not mean we won’t continue to monitor these projects but to focus on only the fight would validate an issue that, once again, has passed away.

After ten years, this time, we should celebrate a successful fight that brought this to the light of day and the fact that California is not ready for ocean desal and it is not ready for us.

Conner Everts is Facilitator for the Environmental Water Caucus, Executive Director of the Southern California Watershed Alliance and co-chair of the Desal Response Group. He is chair of Public Officials for Water and Environmental Reform (POWER) as well as on the board of other organizations, including Amigos de Los Rios. He co-chairs and moderates the Southern California Water Dialogue and the Green LA Water Committee Coalition.

Everts was elected to the Casitas Municipal Water District and was president of the Ojai Basin Management Ground Water Agency. Conner was convener of the California Urban Water Conservation Council and on the state task forces on Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs), Desalination, and the SWRCB recycled water stakeholder process and the Department of Public Health Direct Potable Reuse Advisory Group.

He currently sits on the Mound Basin Sustainable Groundwater Management Agency. But his most important work is as elder advisor to the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water and with the Southern California Steelhead Coalition helping remove dams on the streams where he caught fish as a youth and hopefully others can in the future.

SoCal Water Wars is also recommended by:

The Land Desk

Non-Boring History

Western Water Notes

Mourning Remembrance : A collection of mocking obituaries