Cal Enviro Laws: Weakened by fluid interpretations, money, and politics

Part 1: How Gov. Gavin Newsom intimidated regulators to get Poseidon Water off the hook

Recently I revealed how a proposed ballot initiative (More Water Now) backed by agriculture oligarchs in the San Joaquin Valley would alter California’s constitution and potentially benefit the ocean desalination industry.

It would bypass environmental protection laws, including the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA, which discloses and mitigates or eliminates bad environmental impacts of projects) and the Coastal Act (creator of the Coastal Commission) to fund and build so-called drought resiliency projects.

If passed in the Nov. 2022 election, it would take up to $100 billion from the state’s general fund in yearly increments to build poorly vetted and potentially spurious water-infrastructure projects by decree of the governor’s appointees.

Heavily slanted against conservation (the least expensive and most efficient way of creating reliable water supplies), it would subsidize farmer-oligarchs and developers of environmentally harmful, costly, and unneeded projects, including desalination plants.

My example was a joint proposal by Poseidon Water and the Orange County Water District to build a $1.4 billion ocean desalination plant in Huntington Beach.

The passage of More Water Now, I said, will be “the end of CEQA and the Coastal Act as far as Poseidon is concerned.”

But the deck is already stacked without More Water Now. It’s a matter of degree, but again, the Poseidon project is a good example.

Consider what happened after Gov. Gavin Newsom’s staff interfered in Poseidon’s discharge permit hearings before the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Board last July and August.

At those meetings board member William Von Blasingame put the project in peril by questioning the need for it, a point that relates to Poseidon’s proposed seawater intake system which would use the old AES power plant’s leftover once-through-cooling system (OTC) to suck in 100 million gallons of seawater a day.

OTC systems are 100 percent fatal to micro-marine life and are banned by the state. They are allowed for desalination plants, however, if there is a demonstrated “need” for the project and if less-lethal types of desalination-plants or other water-supply alternatives are infeasible.

The Reasonable Use Doctrine

The Reasonable Use Doctrine is the guide for all environmental protection laws and policies at all levels of government in California. It was added as Article 10, Section 2 of the California Constitution in 1928.

Recognizing the need for conservation, it says that “the waste or unreasonable use or unreasonable method of use of water be prevented.”

The reasonable use of water “shall be self-executing,” it says, and “the Legislature may also enact laws in the furtherance of the policy in this section contained.”

The law “seeks to encourage relatively efficient, economically and socially beneficial uses of the state’s water resources” in accordance to the Reasonable Use Doctrine, says water-law expert Brian E. Gray in the book, Sustainable Water.

Of course, it’s never that simple and the Reasonable Use Doctrine and state laws are nebulous enough to allow room for debate over conflicting interests, as Gray explains.

“The cardinal principle of California water law is that all water rights, and all uses of water, must be reasonable,” he writes. “This seemingly simple and innocuous sentence masks a world of meaning and complexity, however,” because the definition of reasonable use is “interdependent and variable” depending on the situation.

In the case of Poseidon Water, is it reasonable to approve a project that will replace (not increase) 56,000 acre-feet of existing source water (provided by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California) a year at three to four times the cost?

Is the project needed for reliability when the predicted water-supply shortfall for the next 25 years is 10,000/AF or less and when numerous far-less expensive sources, including conservation, and far less environmentally damaging projects are available?

That’s the required discussion that Blasingame tried to have but that Newsom, who also appoints the regional board members, did not want to have.

So Newsom fired Blasingame and replaced him with Tustin City Councilor Leticia Clark—she received about $13,000 from pro-Poseidon labor groups (who see the desalination plants as job opportunities) for her 2020 reelection campaign.

Turns out, as reported by the Los Angeles Times, Newsom is close friends with Jason Kinney, owner of the lobbying firm Axiom Advisors. Kinney is also Newsom’s paid adviser and confidant. Poseidon paid Axiom $575,000 for lobbying services.

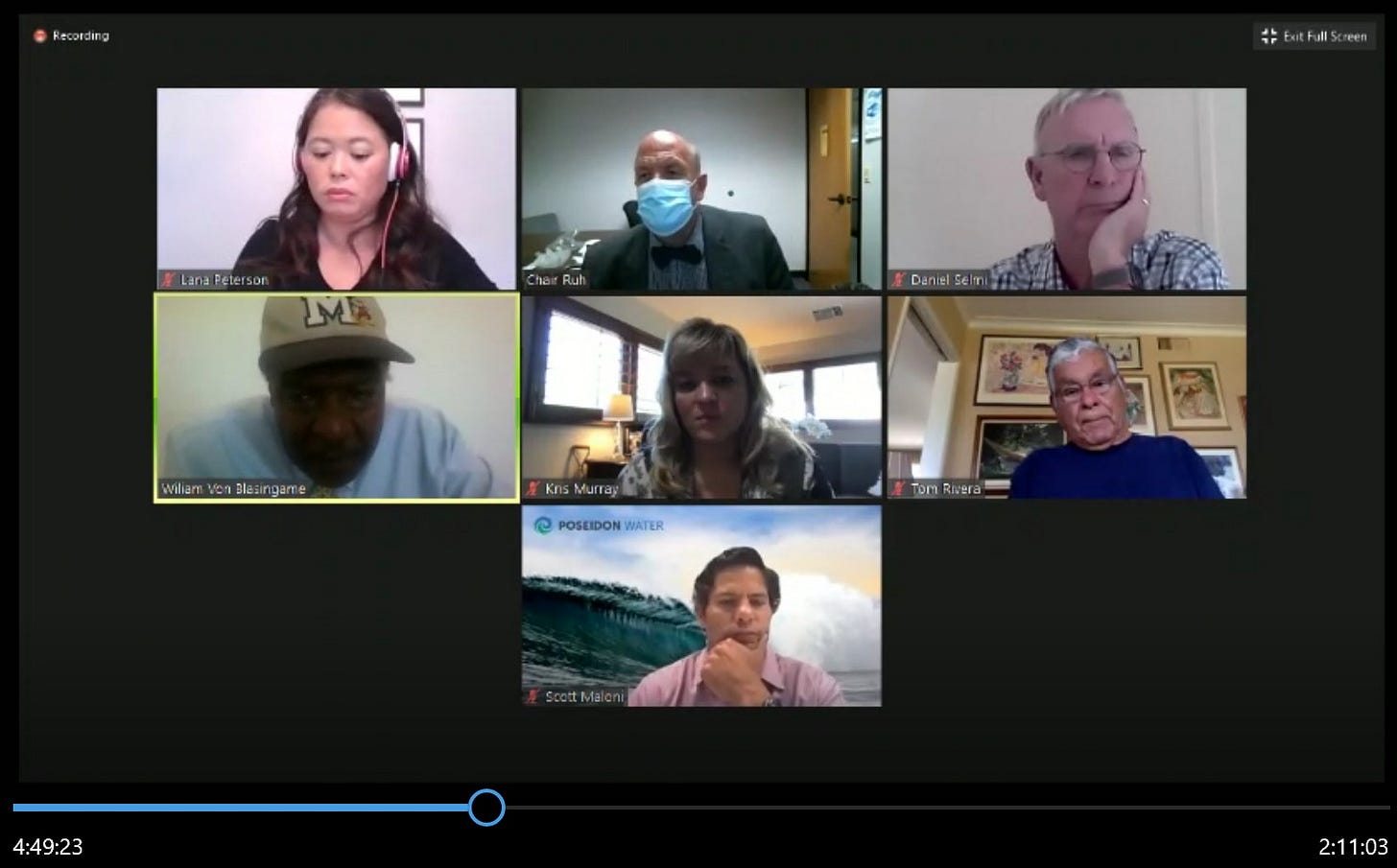

Blasingame’s demise was enveloped by multiple texts and calls to board members and an online meeting initiated by Cal Environmental Protection Agency officials, also appointed by the governor, with the board’s staff, according to the Times.

Some of those contacts took place during the Regional Board’s July/Aug permit hearings, the Times said.

The online meeting included Poseidon VPs Scott Maloni and Peter MacLaggan. Public records indicated that Maloni regularly “inserted himself into staff business,” according to the Times.

The Governor’s message was clear enough: The Regional Board must not bring up the issue of need again.